|

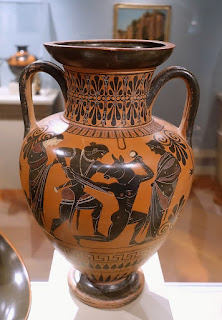

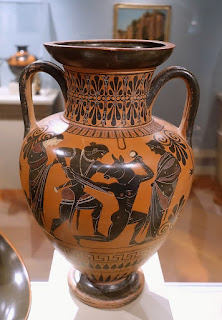

Sappho Painter Name Vase,

late 5th century BC |

This post will look at Greece and the wider Greek world from the years 525BC to 500BC. Firstly a word as to our sources. By and large, the closer we move to the present, the better the sources become. Archaeology will shed some light on the period but not much. Archaeology can give information on settlement patterns and occasional destruction levels, but it cannot tell the stories of the people who lived at this time. For this we are reliant on later writings from the classical world. Unlike the Mesopotamian and Egyptian sources, at least some of which are near contemporary with the events they describe, we have almost no manuscripts from this era, so most of what we hear will be mediated through the words of later writers, particularly Herodotus. This is not necessarily an issue but it should be remembered.

I will also be dealing with elements of Roman history as these arise. I will shortly give Rome its own posts, probably from the year 500BC onwards, but for now there is too little that can be said with certainty about it, so I will mention it along with the events of the Greek world. Roman history will probably also be mentioned in the context of European history in later blogs as well.

I must reiterate that I am not a professional historian, or any other type of historian for that matter. There are certainly mistakes and errors in the sources and I may make mistakes in my interpretations of these sources. Mistakes are particularly likely to occur when dealing with years, as the years in the ancient world do not necessarily correspond exactly to our own. Even professional historians have differing opinions on the exact ordering of events at this time, so exact precision is not likely here. Also, a lot of events have only approximate dating anyway, so some historians will place an event in 520 while another might say 510 and the truth is that no one knows for sure, although some opinions are more founded than others. Also, a lot of writers and poets of the time are active for various periods of time. Thus I might mention Acusilaus as being active in the year 500, but he was doubtless also active in the years around this time as well.

|

| Detail from the Siphnian Treasury in Delphi |

I will briefly recap the year 525 from the last blog. In the year 525 Polycrates, the tyrant of Samos, created a fleet of forty triremes, probably in addition to his existing fleet. This was a very large fleet at the time. It was supposed to have been created to aid the Egyptian king Amasis (who had just died in the previous year) against the imminent Persian invasion. The ships may in fact have been financed by the Egyptians. Manning the ships with his political opponents, possibly hoping that they would die in battle, Polycrates ordered the ships to aid the Persian King Cambyses’ invasion of Egypt, while he remained in Samos.

Egypt fell to the Persians, with or without Samia help on either side. Even though the Samians had proved no help to either side, many Greeks did fight in the conquest of Egypt, on both sides. A tactician named Phanes of Halicarnassus, who had defected from the Egyptians to the Persians was said to have been influential in the Persian victory. Also, when Cambyses had captured Egypt he returned Ladice, an influential lady from Cyrene who had been married to Pharaoh Amasis, back to her homeland with great honour. This probably helped in Cyrene’s decision to submit to the Persians.

|

| Reconstructed detail from the Siphnian Treasury in Delphi |

Those Samians who had been sent to man the ships by Polycrates suspected foul play and turned on Polycrates. A battle may have been fought between the two sides, but if so, Polycrates was victorious over the Samian exiles, and these fled to Sparta asking for aid to overthrow the tyrant Polycrates. The Spartans agreed to help and other Greek states, such as Corinth agreed to join the expedition also.

Some say that these Samians who were sent never came to Egypt, but that when they had sailed as far as Carpathus discussed the matter among themselves and decided to sail no further; others say that they did come to Egypt and there escaped from the guard that was set over them. But as they sailed back to Samos, Polycrates' ships met and engaged them; and the returning Samians were victorious and landed on the island, but were there beaten in a land battle, and so sailed to Lacedaemon.

Herodotus Histories 3:45, written around 440BC

|

| Work attributed to the Lysippides Painter |

In the visual arts, the Lysippides Painter was active around this time. He was a pupil of Exekias and also collaborated with the Andokides Painter. He mainly created black-figure vases.

In poetry, the lyric poet Ibycus flourished around this time. He came from Rhegium, in what is now southern Italy, but lived mainly in Samos during the time Polycrates. His poetry was highly praised at the time but has not been well preserved. We do have some of his verses with us still however.

Theagenes of Rhegium also flourished around this time. In an attempt to defend Homer from the sarcastic quips and moralistic condemnation of writers like Xenophanes, Theagenes is said to have interpreted Homer allegorically. This shows that even at this time the Greeks were beginning to think quite critically about their mythological tradition and how to interpret this in the light of reason. Nothing of what Theagenes wrote has survived however.

|

| Statue of a youth riding a horse, circa 520BC |

Myrtis of Anthedon also flourished around this time. She was a poet of Boeotia, and is said to have been the first of the great lyric poets there. Almost nothing of her works survive however, save a paraphrase of one in Plutarch.

In architecture, around this time, the Siphnian Treasury was built at Delphi. Siphnos was a rich island city-state that had experienced much prosperity. To celebrate their wealth they gifted a treasury building to the priests of the Oracle of Delphi to hold the many votive offerings given by the Greeks. The building itself was a beautiful structure complete with lavish friezes and decorations.

The previous 25 year period had seen the rise of the Persian Empire to the east, and the subjugation of the Ionian Greek city states of Asia Minor by this new power. The interactions of the Greek world and this superpower would prove important for the period that we are examining here.

The Spartans, who were the militarily strongest city in Greece, but who had not previously operated outside of the Peloponnese had been asked by Samian exiles to overthrow the tyrant Polycrates. En route they attacked and overthrew the ally of Polycrates, Lygdamis of Naxos. In place of the tyranny on Naxos they installed an oligarchic government to rule the island.

|

Kore, circa 515BC

traces of paint remain on the statue |

The Lacedaemonians then came with a great army, and besieged Samos. They advanced to the wall and entered the tower that stands by the seaside in the outer part of the city; but then Polycrates himself attacked them with a great force and drove them out. The mercenaries and many of the Samians themselves sallied out near the upper tower on the ridge of the hill and withstood the Lacedaemonian advance for a little while; then they fled back, with the Lacedaemonians pursuing and destroying them.

Herodotus Histories 3:54, written around 440BC

After dethroning Lygdamis the Spartan invasion force, bolstered by Corinthian allies and Samian exiles came to Samos itself. The Samian fleet, doubtless weakened by the defection of forty of their vessels in the previous year, did not attempt to stop the landing. The Spartans began to besiege the city. They pressed the attack, but Polycrates and his mercenaries sallied outside the walls to take the battle to the Spartans. The Spartans eventually repulsed them and the forces of Polycrates were forced to retreat inside the walls, with a few Spartans even following them in. However the main Spartan force could not follow inside the gates and the city held. After waiting forty days in a siege the Spartans eventually left, leaving Polycrates secure in his still surviving city. After surviving the siege, Polycrates now continued with the building work on the huge temple dedicated to Hera on Samos.

So when the Lacedaemonians had besieged Samos for forty days with no success, they went away to the Peloponnesus.

Herodotus Histories 3:56, written around 440BC

After the Spartans had abandoned the siege and returned home, the Samian exiles, who had initiated the invasion did not dare continue the war. They were still a major force however so they sailed to the island of Siphnos, which was quite wealthy at this time. They demanded a loan, but when the Siphnians refused, the Samian exiles attacked and caused a great deal of damage. Eventually they were bought off with a large bribe of 100 talents. After this they sailed, extorting the island of Hydrea from the people of Hermione before eventually settling in Crete, near Cydonia.

|

| Ithyphallic Herm from Siphnos |

The messengers, then, demanded from the Siphnians a loan of ten talents; when the Siphnians refused them, the Samians set about ravaging their lands. Hearing this the Siphnians came out at once to drive them off, but they were defeated in battle, and many of them were cut off from their town by the Samians; who presently exacted from them a hundred talents.

Herodotus Histories 3:58, written around 440BC

The Olympic Games were held this year. Menandros of Thessaly won the stadion race. Milo of Croton won the wrestling. He had now won the boys’ wrestling title once and the men’s wrestling title three times. He was a now a celebrity in the ancient world and probably the most famous athlete of the ancient Olympics.

There is nothing that can said, to my knowledge, for the year 523 in Greece.

In the year 522 the Persian world was thrown into turmoil with the usurpation of Bardiya (or Pseudo-Bardiya), the coup of Darius and the subsequent civil wars and rebellions. While these events were ongoing Polycrates celebrated a massive festival in honour of Apollo, inviting delegations from all over Greece. Oroetes, the Persian satrap of Lydia, may have felt that Polycrates was becoming too great a threat to his own power. Polycrates had in fact previously fought wars against the Ionian states and Oroetes was in any case acting nearly independently of central Persian power, so he probably didn’t care if Polycrates had been friendly with the previous Persian king Cambyses.

|

| Red-figure kylix from the Attica, circa 510's BC |

Polycrates then prepared to visit Oroetes, despite the strong dissuasion of his diviners and friends, and a vision seen by his daughter in a dream; she dreamt that she saw her father in the air overhead being washed by Zeus and anointed by Helios; after this vision she used all means to persuade him not to go on this journey to Oroetes; even as he went to his fifty-oared ship she prophesied evil for him. When Polycrates threatened her that if he came back safe, she would long remain unmarried, she answered with a prayer that his threat might be fulfilled: for she would rather, she said, long remain unmarried than lose her father.

Herodotus Histories 3:124, written around 440BC

Oroetes invited Polycrates to meet him on the mainland, near the city of Magnesia. Herodotus records that this was because Oroetes felt he had been snubbed by Polycrates previously and also says that Polycrates daughter begged her father not to go, alleging that she had seen his death in a dream. Her father went anyway and was captured by treachery. His retinue was also captured, including the distinguished doctor Democedes, who was enslaved by Oroetes. The liberal tyrant of Samos was then tortured and executed before his mangled body was hung up for crucifixion by the Persian satrap. Thus ended the remarkable career of Polycrates. After the news of the death of Polycrates reached Samos, a Samian named Maiandrios usurped the position of tyrant.

|

The crucifixion of Polycrates

by Kozlovsky, 1790 |

But no sooner had Polycrates come to Magnesia than he was horribly murdered in a way unworthy of him and of his aims; for, except for the sovereigns of Syracuse, no sovereign of Greek race is fit to be compared with Polycrates for magnificence. Having killed him in some way not fit to be told, Oroetes then crucified him;

Herodotus Histories 3:125, written around 440BC

Not much can be said for the year 521 save that the usurper Darius had crushed all opposition to his rule as the Great King of Persia. Now the Persian Empire would be reorganised into a much more cohesive and centralised entity. This would have future consequences for the Greek world.

In the year 520, Oroetes, the Persian satrap of Lydia, who had executed Polycrates, was now executed in his turn. He had refused to help King Darius in Darius’ wars and this independent behaviour would not be tolerated by the new king. As Syloson, the exiled brother of Polycrates was friendly to the Persian king, Darius granted him rule over Samos. Syloson was accompanied by Otanes, a Persian noble, and a large army. At first the takeover of Samos seemed to go peacefully, but the brother of Maiandrios mustered the mercenaries and the Persians had to fight for the island. They crushed the attack ruthlessly (remember that the Spartans had been unable to take Samos by siege) and handed over a smoking wasteland to Syloson, for him to rule in the name of Persia.

|

| Antimenes Painter vase showing a sporting competition |

Maeandrius then set sail from Samos; but Charilaus armed all the guards, opened the acropolis' gates, and attacked the Persians. These supposed that a full agreement had been made, and were taken unawares; the guard fell upon them and killed the Persians of highest rank, those who were carried in litters. They were engaged in this when the rest of the Persian force came up in reinforcement, and, hard-pressed, the guards retreated into the acropolis.

Herodotus Histories 3:146, written around 440BC

Also around this time, King Anaxandridas II of Sparta, of the Agiad line, died. He was succeeded by his son Cleomenes I as the Agiad King of Sparta (the Spartans had two kings, descended from two separate family lines, the Agiad and the Eurypontid).

The Olympic Games were also held this year. Anochos of Taranto won both the stadion and diaulos races. Philippos of Croton won an unknown event that is not fully recorded. Damaretos of Heraia won the hoplitodromos, that is, the race in full armour. A citizen of Thebes won the tethrippon, meaning he owned the team of horses that won the chariot race. Finally, Milo of Croton, the famed strongman added to his list of Olympic wrestling victories by winning the men’s wrestling for the fourth Olympiad in a row, not including his victory as a boy previously. His fame as a wrestler had now spread as far as Susa, with King Darius of Persia said to have been a fan of the wrestler.

|

Antimenes Painter Vase showing

Theseus and the Minotaur |

Around this time the Antimenes Painter, an Attic vase painter in the black-figure style, flourished. His style was similar in many ways to the Andokides Painter.

In Etruria, the beautiful Etruscan

Sarcophagus of the Spouses was created for a noble couple interred in the cemetery of Caere. It shows a couple reclining affectionately and is perhaps the most iconic piece of Etruscan art, in my opinion at least.

Around 519 the new Spartan king Cleomenes I was approached by the deposed tyrant of Samos, Maiandrios. Maiandrios had been the treasurer of Polycrates. After Polycrates’ murder he had taken over Samos, only to have the Persians take over the island and give it to the brother of Polycrates, Syloson. Maiandrios must have been hoping to try draw Sparta into a war with Persia to retake Samos. Herodotus recounts that at a dinner party Cleomenes noticed the gold vessels being used to serve and Maiandrios told him to take them as a gift. As this was a bribe, or the beginnings of one, Cleomenes asked Maiandrious to leave Sparta. This is an anecdote however.

Maeandrius sailed to Lacedaemon, escaping from Samos; and after he arrived there and brought up the possessions with which he had left his country, it became his habit to make a display of silver and gold drinking cups; while his servants were cleaning these, he would converse with the king of Sparta, Cleomenes son of Anaxandrides, and would bring him to his house. As Cleomenes marvelled greatly at the cups whenever he saw them, Maeandrius would tell him to take as many as he liked. Maeandrius made this offer two or three times; Cleomenes showed his great integrity in that he would not accept; but realizing that there were others in Lacedaemon from whom Maeandrius would get help by offering them the cups, he went to the ephors and told them it would be best for Sparta if this Samian stranger quit the country, lest he persuade Cleomenes himself or some other Spartan to do evil. The ephors listened to his advice and banished Maeandrius by proclamation.

Herodotus Histories 3:148, written around 440BC

|

| Red-figure kylix from Attica showing maenad |

Also around this time an Aetolian shepherd named Titormus, famous for his raw strength, challenged Milo of Croton, the five time winner of the Olympics, to a challenge of strength. The two men would not wrestle, as Titormus was no wrestler. Instead they went into the Aetolian hills and wrangled bulls and picked up heavy rocks and trees. The two men were well-matched, but in terms of sheer power Titormus was the stronger. Milo is said to have exclaimed in wonder that Titormus was a second Heracles. Thus the most famous strongman in antiquity was beaten.

Around the year 518 the Samian exiles who had helped the Spartans in their failed siege of Samos, plundered the Siphnians and settled in Crete were attacked and beaten by a combined force of Cretans and Aeginatans. Thus their predations came to an end.

|

| Stela of Aristion, circa 510BC |

They themselves settled at Cydonia in Crete, though their voyage had been made with no such intent, but rather to drive Zacynthians out of the island. Here they stayed and prospered for five years; indeed, the temples now at Cydonia and the shrine of Dictyna are the Samians' work; but in the sixth year Aeginetans and Cretans came and defeated them in a sea-fight and made slaves of them; moreover they cut off the ships' prows, that were shaped like boars' heads, and dedicated them in the temple of Athena in Aegina.

Herodotus Histories 3:59, written around 440BC

Around this time, it is said that Leon of Phlius, a tyrant of a small city in the north of the Peloponnese, was discoursing with Pythagoras. Being impressed by his words Leon asked him what was Pythagoras’ occupation. Pythagoras is said to have answered that he was a “philosopher”, meaning “a lover of wisdom”. Whether this was the true origin of the word or not, it is from around this time that the usage of the word philosopher begins. Thales and his compatriots had been philosophers, but had not used the term.

And when Leon, admiring his ingenuity and eloquence, asked him what art he particularly professed, his answer was, that he was acquainted with no art, but that he was a philosopher.

Cicero, Tusculanae Disputationes V.III, written around 45BC

|

| Hero Shrine of Musaeus in Athens |

Around the year 517 there is not much that can be said for certain but we do know that around this time that there was a lyric poet called Lasus of Hermione who flourished at Athens. We also know that the diligent Lasus of Hermione caught another poet/prophet by the name of Onomacritus forging oracles of the semi-legendary Musaeus. We have nothing of the works of either poet, either forged or unforged.

They had come up to Sardis with Onomacritus, an Athenian diviner who had set in order the oracles of Musaeus. They had reconciled their previous hostility with him; Onomacritus had been banished from Athens by Pisistratus' son Hipparchus, when he was caught by Lasus of Hermione in the act of interpolating into the writings of Musaeus an oracle showing that the islands off Lemnos would disappear into the sea.

Herodotus Histories 7.6, written around 440BC

In or around this time the Spartan prince Dorieus, who had chosen exile rather than to be subject to his brother Cleomenes in Sparta, attacked Libya and attempted to found a colony there in Tripolitania. It is said that Dorieus did not consult the Oracle before founding his colony.

|

| Corinthian coinage, circa 515BC |

In the year 516 the Olympic Games were held. Ischyros of Himera won the stadion race. Damaretos of Heraia won the hoplitodromos, the armoured race, for the second Olympiad in a row. Kleosthenes of Epidamnos won the tethrippon chariot race. Timasitheus of Delphi won the pankration. But the most astonishing moment of these Games must have been the victory of Milo of Croton in the wrestling. His first Olympic victory had been in the boy’s wrestling in 540, when he must have been at least sixteen years old. Now, he must have been around fifty years old, but he had since won five more wrestling victories in the men’s wrestling category, dominating the competition since 532. He had also won every competition during this time in the Pythian, Isthmian and Nemean Games. His fame had spread as far as Susa, to the very ears of the great king, and he was said to be so powerful that he could burst a headband simply by clenching and expanding the great veins on his forehead. He was revered throughout the Greek world and honoured and respected in his home city of Croton, where he was probably related by marriage to the philosopher Pythagoras. There may be some confusion in the sources, as there may have been an athletics trainer by the name of Pythagoras, but it is certain that Pythagoras and Milo knew each other personally.

|

| Leagros Group vase painting |

Around the year 515 Ariston of Sparta died and was succeeded by Demaratus as the Eurypontid king of Sparta. Arcesilaus III of Cyrene was slain around this time. He had been a harsh king, who did not accept the constitution of Demonax that his father had accepted. In attempting to take back full power he had been overthrown and fled to Samos with his mother. Gathering an army he had returned to Cyrene and retaken his kingdom before exiling his enemies and granting land to his new supporters. While on a trip to nearby Barca, he was murdered by some of the enemies he had exiled. His mother, Pheretime, fled to Egypt, where she implored the Persian satrap Aryandes to send an army to restore her and her grandson to the kingdom of Cyrene.

But when she learned of her son's death at Barce, she made her escape to Egypt, trusting to the good service which Arcesilaus had done Cambyses the son of Cyrus; for this was the Arcesilaus who gave Cyrene to Cambyses and agreed to pay tribute. So, on her arrival in Egypt, Pheretime supplicated Aryandes, asking that he avenge her, on the plea that her son had been killed for allying himself with the Medes.

Herodotus Histories 4.165, written around 440BC

|

| Kylix by Skythes |

In the arts around this time the Skythes was a vase painter in Attica, painting black-figure and red-figure pottery. His work is a little different from other vase painters at the time, displaying at times a comedic aspect. His name, Skythes, may be a nickname for “The Scythian” perhaps meaning someone who acted like a barbarian.

Around this time Theano, a philosopher who may have been the wife of Pythagoras, flourished. She was part of the Pythagorean community in Croton. She would have been part of the semi-monastic, numerophile community that partly ruled the city of Croton in southern Italy. She was probably the wife of Pythagoras, but may have been the wife of another member of the community, or the wife of nobody. We know too little to say. A number of books were attributed to her in antiquity but none have survived in definite form. Even the quotations attributed to her may be spurious. But it is worth remembering that even in a patriarchal society like the Greek world, that there were still women philosophers.

|

| Leagros Group vase painting |

Around the year 515, although possibly a little earlier, Darius the Great of Persia had sent an expedition to sail down one of the tributaries of the Indus, to reach the ocean and to sail from there to Egypt, coasting the southern edge of Arabia and into the Red Sea. This was an epic voyage of discovery. One of the participants was an Ionian Greek named Scylax of Caryanda. He was probably not leading the voyage but he did write an account, which is now mostly lost. It is from this voyage that the word India comes from. The Sanskrit word for rivers is “Sindhu”, and the modern region is still referred to as Sindh. In Persian the “S” sound in Sanskrit is changed to a “H” sound, so they would have spoken of the region as “Hindhu”. However, Scylax was Ionian, and his dialect did not reflect initial “H” sounds, so he would have referred to the region as “Indos” or “Indike”. This word entered Greek and Latin and eventually to English. Scylax’s work is the first known description of India by an outsider but sadly it is lost and only exists in small quotations by other writers. What little remains suggests that Scylax had listened to some tall tales told by the locals and reported them as fact. Many of the fabulous creatures of the Middles Ages such as the Troglodytes, and Monopthalmi, seem to have come from the pen of Scylax.

But as to Asia, most of it was discovered by Darius. There is a river, Indus, second of all rivers in the production of crocodiles. Darius, desiring to know where this Indus empties into the sea, sent ships manned by Scylax, a man of Caryanda, and others whose word he trusted; these set out from the city of Caspatyrus and the Pactyic country, and sailed down the river toward the east and the sunrise until they came to the sea; and voyaging over the sea west, they came in the thirtieth month to that place from which the Egyptian king sent the above-mentioned Phoenicians to sail around Libya. After this circumnavigation, Darius subjugated the Indians and made use of this sea.

Herodotus, Histories, 4.44, written around 440BC

|

| Pediment decorations from the Temple of Athena Polias |

Around the year 515 there was a temple built on the Acropolis in Athens, which is now known as The Old Temple of Athena Polias. It stood near slightly to the north of the current Parthenon and its foundations are covered in part by the later Erechtheum. It had pediments showing Athena triumphantly fighting giants. It was later destroyed but sections of it were buried by the Athenians and have been rediscovered.

In the year 514 there was an attempted coup in Athens. After the death of Peisistratos his sons Hippias and Hipparchus had taken over. Hippias, the elder son, was in charge of the state and government, while his brother Hipparchus assisted by supervising the cultural life of the city. Hipparchus became infatuated with a younger man named Harmodius. Harmodius was already in a relationship with an older man named Aristogeiton and thus spurned Hipparchus. Infuriated by the refusal Hipparchus, in his capacity as organiser of the festivals, publicly humiliated Harmodius’ sister. Swearing revenge, Harmodius and his lover Aristogeiton determined to slay Hipparchus and Hippias and end the tyranny. Aristotle gives a slightly different account to Thucydides, alleging that it was another member of Peisistratos’ family who was involved but whether it was Hipparchus or Thessalos who was infatuated with Harmodius makes little difference.

|

Foundations of the Old Temple of Athena Polias in the

foreground (the Erechtheum was built later) |

At last the festival arrived; and Hippias with his bodyguard was outside the city in the Ceramicus, arranging how the different parts of the procession were to proceed. Harmodius and Aristogeiton had already their daggers and were getting ready to act, when seeing one of their accomplices talking familiarly with Hippias, who was easy of access to everyone, they took fright, and concluded that they were discovered and on the point of being taken;

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, 6.57, written around 400BC

The two lovers had planned to murder Hippias first and then Hipparchus. There were a number of conspirators that were aware of the plot. The conspirators had planned to strike during the Panathenaic Festival, when a number of the citizens would be armed with ceremonial weapons for the procession to the Acropolis. The parade was being organised in the Keramaikos cemetery area of Athens, preparing to march into the city. While this was happening the conspirators saw one of their party casually chatting to Hippias, who was well-guarded and they assumed that they had been betrayed. Thinking that Hippias could not be slain, they tried frantically to find Hipparchus and cut him down without warning. Harmodius was slain by Hipparchus’ guards, but his lover Aristogeiton escaped.

|

Later statue group (Roman copy of a

Greek original from the 5th century)

showing the tyrannicides in the act of

assassinating Hipparchus |

They rushed, as they were, within the gates, and meeting with Hipparchus by the Leocorium recklessly fell upon him at once, infuriated, Aristogeiton by love, and Harmodius by insult, and smote him and slew him. Aristogeiton escaped the guards at the moment, through the crowd running up, but was afterwards taken and dispatched in no merciful way: Harmodius was killed on the spot.

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, 6.57, written around 400BC

News reached Hippias of what had happened, but, not losing his composure, he quietly disarmed the citizenry and started searching the people, arresting those who were carrying concealed weapons. Aristogeiton and a number of others died under torture. Leaina, a courtesan who was a lover of one of the two men, also died under torture and it is said that she did not give up the names of the conspirators.

Hippias now became paranoid about his security and began to see plots everywhere. In archaic Greece, the word 'Tyrant' had few bad connotations. There were evil tyrants such as Phalaris, but also relatively cultured tyrants such as Polycrates. However, Hippias now began to oppress the people of Athens, arresting the citizens, torturing them and executing them on the slightest pretext or the flimsiest denunciation. He also began to seek a refuge in Lampsacus, far from Athens, in case he should ever have to flee the city.

|

5th century red-figure vase showing

Harmodius and Aristogeiton in the act

of slaying Hipparchus |

In later years, the two lovers, Harmodius and Aristogeiton, became symbols of Athenian freedom and democracy. They were known as the Tyrannicides, those who slew the tyrant, despite having only actually killed his brother. A famous statue group of the two men in the act of slaying Hipparchus was placed in the Agora. When it was later stolen by the Persians, the Athenians replaced it. While all the statues are now lost we can see the Roman copies, which still exist to this day. Even Leaena, the courtesan who did not betray the plotters even under torture, was remembered with a statue. It was not thought appropriate to have a statue of a courtesan, but a symbolic bronze lion was placed on the Acropolis, as her name meant “lioness”. The lion was made without a tongue, symbolising her silence.

How Aristogeiton and Harmodius delivered Athens from the tyrant's yoke, is known to every Greek. Aristogeiton had a mistress, whose name was Leaena. Hippias ordered her to be examined by torture, as to what she know of the conspiracy; after she had long borne with great resolution the various cruelties that were exercised on her, she cut out her tongue with her own hand, lest the further increase of pain should extort from her any disclosure. The Athenians in memory of her erected in the Propylaea of the Acropolis a statue of a lioness in brass, without a tongue.

Polyaenus, Stratagems, 8.45, written around AD163

|

Drawing by Hans Holbein showing Leaena

tearing out her tongue rather than betraying

the tyrannicides |

Herodotus mentions the career of the Greek doctor Democedes. Originally from the Greek city of Croton in Sicily, he was a famed doctor who had gone to Samos to serve under Polycrates. When Polycrates was captured and slain by the Persian satrap Oroetes, the doctor was held as a prisoner of war. When Oroetes was executed on Darius’ orders, these prisoners were sent inland to the Great King. When Darius sustained a leg injury Democedes was supposedly able to assist and restore the king to full health.

Around the year 514 the Persian queen Atossa, daughter of Cyrus the Great, became ill with what appears to be the first recorded case of breast cancer, and possibly the earliest record of cancer. Democedes was able to cure her, presumably by excising the growth, although this is not recorded. Democedes was probably a surgeon rather than a doctor as we would know it.

A short time after this, something else occurred; there was a swelling on the breast of Atossa, the daughter of Cyrus and wife of Darius, which broke and spread further. As long as it was small, she hid it out of shame and told no one; but when it got bad, she sent for Democedes and showed it to him. He said he would cure her, but made her swear that she would repay him by granting whatever he asked of her, and said that he would ask nothing shameful.

Herodotus, Histories 3.133, written around 440BC

Around this time the Greek colony at Tripolitania, founded and led by the self-exiled Spartan prince Dorieus, was overthrown by Libyan tribes. The tribes were allied to the Carthaginians, but it was not clear that the Carthaginians had taken part in the attack themselves. They would certainly not have wanted to see Dorieus' colony succeed.

|

| Darius of Persia |

In the year 513 King Darius of Persia made a great expedition against the Scythians in Europe. He crossed the Bosphorus, bridging it with a great pontoon bridge of boats. After this his armies subdued all of the Greek cities of the region, as well as the Thracian tribes south of the Danube. As his navy had moved into the Black Sea they were able to bridge the Danube as well and chased the Scythian armies across the steppe, possibly moving as far as the Volga. They were unable to bring the Scythians to battle however and they had to return to the bridges, short on supplies. The Ionian Greeks had been left in charge of the bridges and had the possibility of betraying the Persian king. The tyrant of Miletus (all of the Ionian cities had been given tyrants by the Persians) Histiaeus, argued to stay loyal and the bridges of the Danube were preserved against the Scythians until Darius could make it back across.

When these accepted Histiaeus' view, they decided to act upon it in the following way: to break as much of the bridge on the Scythian side as a bowshot from there carried, so that they seem to be doing something when in fact they were doing nothing, and that the Scythians not try to force their way across the bridge over the Ister (Danube); and to say while they were breaking the portion of the bridge on the Scythian side, that they would do all that the Scythians desired.

Herodotus, Histories, 4.139, written around 440BC

This act of loyalty was not forgotten by Darius. To the other Greeks, the main import of this expedition was that Darius had left Megabazus in Europe with a large army. The Persians had now established a permanent presence in Europe, with their new province stretching up perhaps as far as the Danube.

|

Ruins of Temple of Heracles in Agrigentum,

late 6th century BC |

Meanwhile in Libya around this time, the armies of Aryandes, the Persian satrap of Egypt, had finally conquered Cyrene and Libya. Pheretime, the mother of the murdered king Arcesilaus III, had begged Aryandes to retake Cyrene for her grandson. Pheretime died around this time, of a skin disease, that was seen by the Greeks as divine judgement for having brought such war on her people. After a long siege and betrayal, Aryandes’ men took the city, slew those who had revolted and placed Battus IV on the throne, to rule as a vassal of Persia.

At this time, Aryandes took pity on Pheretime and gave her all the Egyptian land and sea forces, appointing Amasis, a Maraphian, as general of the army, and Badres of the tribe of the Pasargadae, admiral of the fleet. But before despatching the troops, Aryandes sent a herald to Barce to ask who it was who had killed Arcesilaus. The Barcaeans answered that it was the deed of the whole city, for the many wrongs that Arcesilaus had done them; when he heard this, Aryandes sent his troops with Pheretime. This was the pretext; but I myself think that the troops were sent to subjugate Libya.

Herodotus, Histories, 4.167, written around 440BC

In the year 512 Megabazus, the Persian commander in Thrace, forced Amyntas I of Macedon to submit to Persian rule. This extended Persian control to the edges of Thessaly, although Macedonia was not organised into a satrap.

|

Remains of the Theatre of Dionysos in Athens, viewed

from the Acropolis |

The Olympic Games were held in this year, with Pheidolas of Corinth winning the horse race, Timasitheus of Delphi winning the pankration. Milo of Croton is said to have returned to the ring to try for his seventh Olympic victory, but the age had finally caught up with Milo. His younger opponent, Timasitheus of Croton, was also from his home city and unable to defeat Milo with strength, but as the match went on Milo became too tired to continue and was finally defeated at the games. He had had a heroic run of victories. The dramatic defeat of Milo of Croton was matched by the achievements of Phanas of Pellene who won the stadion, the diaulos and hoplitodromos, making him the first to have won all three races. This type of agility and raw sporting prowess had not been seen since the age of Chionis of Sparta, nearly 150 years earlier. The Spartans were so worried about Phanas’ achievements that they rewrote the text of the monument to Chionis, noting that the reason that he had never won the hoplitodromos was because the armoured race was not introduced at this time.

|

Statue of Milo of Croton

in the Louvre |

Around the year 511 Phrynichus, a tragic poet, wrote a play and won the tragedy competition at the Great Dionysia. Very little of Phrynichus’ work survives but it was a sign that tragedy was becoming more formalised, as the Great Dionysia festival and drama competitions formalised. Around this time there would only be a chorus (often split in two) and a single actor on the stage, who would interact with the chorus.

In the year 510, in the south of Italy, the city of Sybaris was one of the wealthiest in the region and their citizens were noted for their luxury and decadent lifestyles. In fact, even in English, “

sybarite” or “

sybaritic” are words synonymous with “

hedonist” and “

hedonistic” respectively. Supposedly Sybaris and Croton had once been allies, but that Sybaris had been taken over by a tyrant called Telys, who banished most of the leading citizens of the city. These fled to Croton, who went to war with Sybaris. At this point Croton was ruled by the Pythagorean philosophers. Their athletes were the wonder of the world, with Milo of Croton only being beaten by another strongman of Croton. Milo is said to have led the armies of Croton, dressed as Heracles with a club and lionskin, to destroy the Sybarites. The battle is not well-recorded, but it is clear that the people of Croton won a bloody victory. The supporters of Telys were slain or expelled and the remnants of the pleasure-loving city of Sybaris were forced into an alliance with Croton. This was the high point of the city of Croton in its history.

It is said that the self-exiled Prince Dorieus of Sparta was killed in this battle, fighting on the side of Croton against Sybaris. After the failure of his expedition to Libya, he had wanted to found another colony in western Sicily, but this desire died with him it would seem.

|

| Coin of Sybaris from the late 6th century BC |

While the Greek states of southern Italy were battling, there was turmoil in Athens. Hippias, the tyrant son of Peisistratos, had become paranoid and cruel after the murder of his brother during the failed coup of Harmodius and Aristogeiton. Hippias now made plans to ally himself with the Persian aligned tyrant of Lampsacus and a marriage alliance was concluded between the families of the two tyrants. But the unpopularity of Hippias, the wealth and power of the Alcmaeonidae family (enemies of Peisistratos and his sons) and the fear of the Spartans made for Hippias’ downfall.

|

| Ball player grave stela base in Athens, circa 510BC |

A small Spartan invasion force was defeated by Hippias, but a larger Spartan army under the command of Cleomenes I soon invaded Athens. The Athenians made no real attempt to stop them and Hippias retreated to the Acropolis with his bodyguard. However, fighting soon ceased when the Spartans captured Hippias’ children and used them as hostages for bargaining. In a negotiated settlement Hippias was allowed to leave the city with his family and his supporters in banishment.

The Lacedaemonians would never have taken the Pisistratid stronghold. First of all they had no intention to blockade it, and secondly the Pisistratidae were well furnished with food and drink. The Lacedaemonians would only have besieged the place for a few days and then returned to Sparta. As it was, however, there was a turn of fortune which harmed the one party and helped the other, for the sons of the Pisistratid family were taken as they were being secretly carried out of the country. When this happened, all their plans were confounded, and they agreed to depart from Attica within five days on the terms prescribed to them by the Athenians in return for the recovery of their children. Afterwards they departed to Sigeum on the Scamander.

Herodotus, Histories, 5.65, written around 440BC

|

| Later painting showing the Pythagoreans greeting the dawn |

The Leagros Group of Attic, black-figure vase painters were also active around this time. They were a group of painters who created hundreds of vases that have been preserved.

In architecture, the huge Temple of Olympian Zeus that had been under construction by the Peistratids was abandoned. The vast size of the temple and the association with the tyrants made the project distasteful to the Athenians. The building was abandoned and left vacant for the following centuries until the Roman era, when a new temple would be constructed on similar dimensions to the abandoned Peisistratid temple.

The downfall of Hippias led to one temple being abandoned, but for another one to be built. The Temple of Apollo in Delphi had been burned down in a fire. The temple was replaced by a new one that was financed by the Alcmaeonid family from Athens. The Alcmaeonidae had been instrumental in the downfall of Hippias and helped to finance a new temple to Apollo, possibly as an offering to the gods for restoring them to their homeland.

|

| Coin of Darius I of Persia |

In Croton there was a flowering of philosophical, scientific, mathematical and mystical thought. Brontinus was a follower of Pythagoras, but no genuine works of his survive. There are also a number of women philosophers known from this period, such as Arignote, Damo and Myia. These were said to be daughters of Pythagoras and Myia is also said to have been married to Milo of Croton, the famous wrestler, strongman and general who had brought such glory to his city. While they were known in antiquity, sadly, none of their works survive. A son of Pythagoras, by the name of Telauges, was also in Croton around this time, but it is not clear if he wrote any philosophical works.

Around this time, Democedes, the famed surgeon from Croton, escaped from Persia. He had travelled to Samos to serve with Polycrates, was captured by the Persians when Polycrates was ambushed and taken as a slave to Persia, where he rendered great services to Darius and Atossa and was treated well by the royal family. However, Democedes longed to escape and return to his homeland, so he persuaded Atossa to ask the king to let him take part in a scouting expedition of Greece. This was a similar expedition to that of Scylax of Caryanda around 515.

Darius agreed to send Democedes, but when the Persian ships reached Tarentum in southern Italy Democedes made his escape. The local king of Tarentum held back the Persians under false pretences, buying the fugitive time to escape. Democedes made it to Croton, where the Persians followed him. Croton had heard of the power of the Great King, but they still protected their own and refused to let the Persians take him.

|

| Coin of Tarentum from late 6th century BC |

The Persians sailed from Tarentum and pursued Democedes to Croton, where they found him in the marketplace and tried to seize him. Some Crotoniats, who feared the Persian power, would have given him up; but others resisted and beat the Persians with their sticks. “Men of Croton, watch what you do,” said the Persians; “you are harboring an escaped slave of the King's. How do you think King Darius will like this insolence? What good will it do you if he gets away from us? What city will we attack first here? Which will we try to enslave first?” But the men of Croton paid no attention to them; so the Persians lost Democedes and the galley with which they had come, and sailed back for Asia

Herodotus, Histories, 3.137, written around 440BC

Democedes then paid a large sum to marry the daughter of Myia and Milo. Democedes was the most famed doctor in the Greek world at this time. His mother-in-law was a famed philosopher. His father-in-law was the greatest wrestler the Greek world had ever seen. His grandfather-in-law was the most famous philosopher of his time and is still remembered today. Any family gatherings must have been interesting.

|

| Painting showing the death of Milo of Croton |

But Democedes gave them a message as they were setting sail; they should tell Darius, he said, that Democedes was engaged to the daughter of Milon. For Darius held the name of Milon the wrestler in great honor; and, to my thinking, Democedes sought this match and paid a great sum for it to show Darius that he was a man of influence in his own country as well as in Persia.

Herodotus, Histories, 3.137, written around 440BC

Around the year 509 Milo of Croton died. This legendary figure is given a legendary death. It is said that he was in the forest, ripping apart tree trunks with his bare hands, when his hand became caught in a tree and he was unable to pull it loose. He was trapped and even his vast strength was unable to extricate him. As he was working to pull himself free he was caught by a pack of wolves. Trapped and with only one arm to fight he was eaten alive by the wolves. It is a terrifying and tragic end for a man whose life had been full of glory. It is of course, almost certainly mythical, but it is a story worth remembering.

|

Strangford Apollo

circa 500BC |

Whether or not Milo was dead, he disappears from history. The rule of the Pythagoreans in Croton was ending. A champion of the people, named Cylon of Croton, rose up and led a revolt against the philosophers. Later writers speak of the Pythagoreans being attacked and burned to death in a meeting house, but it is very likely that Pythagoras and his followers were merely exiled.

Meanwhile in Athens no tyrant had taken over the city after the expulsion of Hippias. Instead the people were split between the followers of Cleisthenes and the followers of Isagoras. Because both men had no firm foundation of power, both looked to give the people concessions. Isagoras was linked to Spartan power however, so Cleisthenes was forced to rely more fully on the people for his support.

Athens, which had been great before, now grew even greater when her tyrants had been removed. The two principal holders of power were Cleisthenes an Alcmaeonid, who was reputed to have bribed the Pythian priestess, and Isagoras son of Tisandrus, a man of a notable house but his lineage I cannot say. His kinsfolk, at any rate, sacrifice to Zeus of Caria. These men with their factions fell to contending for power, Cleisthenes was getting the worst of it in this dispute and took the commons into his party.

Herodotus, Histories, 5.66, written around 440BC

In Boeotia, to the north of Athens, the small city-state of Plataea revolted against Thebes, the foremost power in Boeotia, and made an alliance with Athens. Even with Athens divided, they seem to have been able to fight and defeat the Thebans sufficiently that Plataea became a firm ally of Athens.

|

| Model of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus |

In Rome Lucius Tarquinius Superbus (Tarquin the Proud) was king. He had taken power around 535, according to the traditional dating, by dethroning and killing the previous king, Servius Tullius. Tarquin the Proud had been an energetic king. He had curtailed the rights of the people and the aristocrats, but had kept them busy with continuous warfare and building projects. His father, Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, had supposedly begun work on a huge temple to Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill. Tarquin the Proud continued this. This temple was vast. In fact, it would have been a large temple even in the Greek world. The statue of Jupiter within it was made of terracotta and the red clay face of the statue became synonymous with victory; so much so that later Roman generals would paint their faces red when the entered the city in triumph after victories.

|

| Etruscan lions from the late 6th Century BC |

Here his first concern was to build a temple of Jupiter on the Tarpeian Mount to stand as a memorial of his reign and of his name, testifying that of the two Tarquinii, both kings, the father had made the vow and the son had fulfilled it.

Titus Livius, Ab Urbe Condita, 1.55, written around 18BC

Tarquin not only worked on the temple, but he also cleared a lot of ground on the Capitoline Hill, deconsecrating the Sabine shrines near the Tarpeian Rock. The only shrine that was not deconsecrated was the shrine of Terminus, the god of boundaries. This was held to be a good omen, as it portended that the boundaries of Rome would never move inwards. The people were also forced to work on greatly expanding the Cloaca Maxima, an open sewer that would drain away the waste water and sewage of the city of Rome.

|

| Etruscan helmets from the 5th and 6th centuries BC |

Tarquin the Proud also pursued extensive wars, fighting against the Volsci and the cities of Gabii and Ardea. The city of Gabii could not be taken by force so he sent his son to inveigle his way into the city and become its ruler. His son did this and then sent a messenger to ask to advice. Tarquin the Proud did not answer the messengers request but merely walked through a garden knocking the heads of the tallest poppies off with his stick. This was interpreted by his son as an injunction to murder the outstanding citizens of Gabii and thus make the city vulnerable to Rome. This is an interesting story, but it is extremely similar to a story told by Herodotus about the tyrants of Corinth, so it is probably a later tale.

|

Chiusi Painter

Ajax and Achilles playing dice

circa 510BC |

Another strange tale is that during this time the Cumaean Sibyl came to Rome, offering nine books for sale at a high price. The king refused to purchase them, so the Sibyl departed and burned three of the books. The Sibyl then returned with six books, offering to sell these to the king, but at the same price. The king thought this was foolish, so he refused to purchase them, upon which the Sibyl burned another three books. Finally when the last three books were offered for sale, Tarquin the Proud bought the books, as much from curiosity as piety. These books were known as the Sibylline Books and were said to tell the whole future of the city of Rome. The reason why things were occasionally unclear was because a third of the books had been burned. When the Republic was in danger the priests would consult the books and tell the people what had been foretold.

This was an important ritual, but we now know that the books were forged by the people at the time. Later spurious copies of the books have survived, but these are even later forgeries. Like all of the stories of Rome at this time, it is a good story; the idea that the destiny of the city was foretold and that each setback was merely a dark chapter on an inevitable road to greatness.

According to Livy, Tarquin had angered the common people, by his constant wars, and building and by his absolute rule. He had also angered the nobility by his execution of any prominent men who opposed him. The spark for an uprising occurred while his army was besieging Ardea. His son, Sextus Tarquinius, is said to have raped Lucretia. Lucretia was a noble lady who was married to, Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, a powerful nobleman and relative of the royal family. Lucretia is said by Livy to have met her husband, making sure that several witnesses were present, before revealing the truth and then dramatically stabbing herself and committing suicide. Those present, including her husband Collatinus and a noble relative named Lucius Junius Brutus swore revenge against Tarquin and his family.

|

Suicide of Lucretia, showing the

previous rape in the background

Painting by Ambrosius Benson

around 1540 |

Brutus, while the others were absorbed in grief, drew out the knife from Lucretia's wound, and holding it up, dripping with gore, exclaimed, “By this blood, most chaste until a prince wronged it, I swear, and I take you, gods, to witness, that I will pursue Lucius Tarquinius Superbus and his wicked wife and all his children, with sword, with fire, aye with whatsoever violence I may; and that I will suffer neither them nor any other to be king in Rome!”

Titus Livius, Ab Urbe Condita, 1.59, written around 18BC

Brutus had been supposedly given this nickname of a “brute” because he feigned stupidity and insanity to ensure that Tarquin did not kill him. Upon the death of Lucretia he went to the Forum, telling the tale of what had happened and rallying the outraged Romans to his cause. Upon reaching the Forum he summoned an assembly and whipped the gathering of citizens into a revolutionary frenzy. Tullia, the wife of Tarquin, fled the city to the Roman army that was besieging Ardea. With the corpse of Lucretia still displayed in the Forum, the Romans under Brutus declared that the monarchy was at an end and that from henceforward Rome would be a Republic.

He spoke of the violence and lust of Sextus Tarquinius, of the shameful defilement of Lucretia and her deplorable death, of the bereavement of Tricipitinus, in whose eyes the death of his daughter was not so outrageous and deplorable as was the cause of her death. … He spoke of the shameful murder of King Tullius, and how his daughter had driven her accursed chariot over her father's body, and he invoked the gods who punish crimes against parents.

Titus Livius, Ab Urbe Condita, 1.59, written around 18BC

|

Later bust of Brutus

Capitoline Museum |

Upon hearing of the revolt Tarquin left the camp at Ardea and hurried towards the city to try cajole the citizens into obedience again. But the city was locked against him. Meanwhile messengers from Rome had reached the city of Ardea, where they gave letters to the army. The generals read out the letters and the soldiers voted to overthrow the kings and support the new republic. Devoid of his city and his army, Tarquin and his family fled into exile.

The Tarquins were now in exile and Rome was ruled by two new consuls, Collatinus and Brutus, who had been asked to oversee matters of the state in the absence of kings. Brutus proposed to the people that all those bearing the name Tarquin should be banished from the state to prevent the return of the kings. This meant that Collatinus had to resign and be banished. Conveniently it was only those with the name Tarquin who were affected, despite the fact that Brutus was also related to the Tarquins.

For the name of one of the consuls, though he gave no other offence, was hateful to the citizens. “The Tarquinii had become too used to sovereignty. It had begun with Priscus; Servius Tullius had then been king; but not even this interruption had caused Tarquinius Superbus to forget the throne or regard it as another's; as though it had been the heritage of his family, he had used crime and violence to get it back; Superbus was now expelled, but the supreme power was in the hands of Collatinus. The Tarquinii knew not how to live as private citizens. Their name was irksome and a menace to liberty.”

Titus Livius, Ab Urbe Condita, 2.2, written around 18BC

|

Later statue from Vienna

showing Mucius Scaevola with

hands in the flames |

A conspiracy was formed among some of the nobles of Rome to bring back the Tarquins. This was discovered by a slave and the guilty parties were executed by the state under the authority of Brutus. According to Livy, Brutus’ own sons had betrayed the state and as his duty to the state outweighed all other duties, Brutus oversaw the execution of his own children.

The culprits were stripped, scourged with rods, and beheaded, while through it all men gazed at the expression on the father's face, where they might clearly read a father's anguish, as he administered the nation's retribution.

Titus Livius, Ab Urbe Condita, 2.5, written around 18BC

After the failed plot in Rome, Tarquin the Proud gathered his Etruscan allies, primarily from the nearby city of Veii and marched on Rome. The sides fought a hard-fought battle at Silva Arsia, but despite high casualties on both sides the Romans claimed the victory and Tarquin had to retreat once more.

Tarquin then appealed to the king of Clusium, Lars Porsena, who had a fearsome reputation at that time among the Italians. Some young Romans vowed to assassinate Lars Porsena. One Roman noble, named Mucius Scaevola reached Clusium, but assassinated the wrong target. Facing the threat of torture and death the captured Mucius held his hand in a lit brazier to show that he feared neither pain nor death. Impressed by the courage of the young man, Lars Porsenna let him go.

|

Painting on a dish from 1542 showing Horatius

Cocles defending the bridge |

Lars Porsena gathered a large army and attacked Rome from the west, from the right bank of the river. The Romans sent an army to meet him but their forces were outnumbered and they were beaten back in disorder across the Pons Sublicius, which was at this point the only bridge across the Tiber. A young soldier named Horatius Cocles and two other more experienced soldiers held the bridge for a time against the attackers, allowing the retreating Romans to cross and then to break the bridge behind them. Eventually the other two retreated while Horatius stood alone until he heard that the bridge was broken and that he should flee. He is said to have dived into the river and to have swam across the Tiber to be received with cheers by the Roman force. The whole account is almost certainly legendary, but it is probable that, despite the power of Lars Porsena, that the Tarquins did not retake the city.

But after a while he forced even these two to leave him and save themselves, for there was scarcely anything left of the bridge, and those who were cutting it down called to them to come back. Then, darting glances of defiance around at the Etruscan nobles, he now challenged them in turn to fight, now railed at them collectively as slaves of haughty kings, who, heedless of their own liberty, were come to overthrow the liberty of others.

Titus Livius, Ab Urbe Condita, 2.10, written around 18BC

|

Later painting by Charles Le Brun showing

Horatius Cocles defending the bridge |

All of the stories about the birth of the Republic are almost certainly legendary, but they are wonderful tales. Despite being sceptical of them I feel that they nevertheless deserve to be remembered.

The dates of all of these stories should be treated with some scepticism. I have placed them all in or around the year 509, which is kind of the traditional date for the founding of the Republic. However, this main date may be incorrect and the other stories might have happened years later, if they happened at all. The important thing is that Rome expelled its kings and became a Republic around this time.

There clearly were some upheavals in Italy around this time, as the Etruscan town of Acquarossa seems to have been destroyed in or around this time. It is probably unrelated to the struggles at Rome however.

In 508 Isagoras was elected as eponymous archon, which gave him a certain amount of power in the city of Athens. He decided to be rid of his rival Cleisthenes once and for all. To do this he called in the Spartan king Cleomenes I, who was on friendly terms with Isagoras. Cleomenes had removed Hippias from power so it seemed easy for him to remove Cleisthenes. Cleisthenes and a large number of his supporters were banished, on the questionable reasoning of the curse of the Alcmaeonids. However the Athenian people would no longer stand for such Spartan interference. This was not the removal of a bloody and dangerous tyrant. This was a removal of a popular leader for no greater reason than a personal grudge.

|

| Sappho Painter Lekythos |

When Cleomenes had sent for and demanded the banishment of Cleisthenes and the Accursed, Cleisthenes himself secretly departed. Afterwards, however, Cleomenes appeared in Athens with no great force. Upon his arrival, he, in order to take away the curse, banished seven hundred Athenian families named for him by Isagoras. Having so done he next attempted to dissolve the Council, entrusting the offices of government to Isagoras' faction.

Herodotus’ Histories, 5.72, written about 440BC

The people fought back and Isagoras and the Spartan king Cleomenes were besieged briefly on the Acropolis before they made an agreement and left the city; King Cleomenes to return to Sparta and Isagoras to go into banishment. 300 of Isagoras’ supporters were executed. Among those executed was Timasitheus of Delphi who had been a victor in the Olympic Games and was renowned for his bravery. Cleomenes returned to Sparta to summon an army to put Hippias back in power in Athens, but the Corinthians and other allies of the Spartans disagreed and Athens was left in peace. This was the moment that Athens became a true democracy.

The Council, however, resisted him, whereupon Cleomenes and Isagoras and his partisans seized the acropolis. The rest of the Athenians united and besieged them for two days. On the third day as many of them as were Lacedaemonians left the country under truce.

Herodotus’ Histories, 5.72, written about 440BC

|

Pnyx Hill. The flat space was where the Assembly met.

The speakers platform was added later and is to the right

of the picture. The Areopagus can be seen in the left

background. The Agora lies to the left. The Acropolis is

visible in the background and behind it,

Mount Hymettus |

As Cleisthenes needed the people he used his influence to reorganise the citizenry into “

demes”, which would act as the voting blocks of the citizens instead of other previous loyalties of clans and families. The previous reforms of Solon and Peisistratus had laid the foundation for these reforms. New tribes were created, forming ten artificial groupings to split up the people of Athens. These cut across previous loyalties and both deme and tribe served to foster loyalty to the city as a whole. A new Council of five hundred citizens was formed. These members were directly elected. The main democratic body was however the “

ecclesia” or the Assembly, which dated back to Solon. These comprised the free male citizens of Athens who could vote directly on matters of government at meetings of the Assembly. There was no building in the city large enough for such a group, usually around six thousand people, so the Assemby met on the nearby Pnyx Hill.

|

Achilles binding the wounds of Patroklos,

by the Sosias Painter |

The final reform of Cleisthenes was to allow the people of Athens to cast a vote to expel anyone from the city who was thought to be a danger to the city, even if they had committed no crime. This was known as ostracism. The name comes from the fact that the Athenians would write the name of the person they feared most on a shard of pottery (known as

ostraca, hence, ostracism) and if a sufficient number of the same name were found, this person would be forced to leave the city for ten years, although their property would still be theirs if they chose to leave it in the city. These were some of the reforms of Cleisthenes and the flowering of the first major democracy known to the world. In Greek, the “people” were known as the “

demos” and the word for power was “

kratia”. So democracy could be said to be literally “people power”.

This new people-power was to be tested almost immediately. The Thebans were angered at their defeat by the Plataeans and Athenians and thus they made an alliance with the wealthy island state of Aegina, which was a rival of Athens. The Aeginetans seem to have had no great interest in actually fighting, but they did send some sacred statues of the Aeacidae to Thebes. Unluckily for the Thebans, these statues proved of limited use and the Thebans were defeated once more.

The Olympic Games were also held in 508. Isomachus of Croton won the stadion race. Kalliteles of Sparta won the wrestling competition. The sons of Pheidolas of Corinth won the horse racing. Phrikias of Pelinna won the hoplitodromos. Finally, Pantaros of Gela won the tethrippon, meaning that he owned the team of horses that won the chariot race.

|

Model of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus

as it would have looked surrounded by later buildings |

In the year 507 the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill in Rome was finally dedicated by the officials of the new Republic. It was a vast construction and may have been 60m x 60m. There were certainly larger Greek temples, but this would have been considered to have been a very large building for the standards of Italy at the time.

In the year 506 the people of Aegina launched a raid on Athens. They were allied with Thebes and the Thebans may have implored them to do more to aid them. This was apparently a war that was begun without warning, as the Athenians received no herald. This was not the beginning of the rivalry between Aegina and Athens, but it was certainly a great escalation of the hatred between the two states.

There is little that can be said for the year 505 save that the Sabines and the Romans fought each other that year and the next. Histiaeus of Miletus was asked by King Darius of Persia to come to Susa where he would be a guest friend of the Great King. Histiaeus appointed Aristagoras as a replacement tyrant of Miletus in his stead.

In the year 504 the Olympic Games were held. Isomachus of Croton won the stadion race for the second time. A man named Titas won an unknown event. Thessalos of Corinth won the diaulos race. Phrikias of Pelinna won the hoplitodromos for the second time. Philon of Korkyra won the boys stadion. King Demaratus of Sparta won the tethrippon, meaning that he owned the team of horses that won the chariot race.

Also in the year 504 the Romans and the Sabines fought another war. The Greek city of Cumae in Italy seems to have won a victory against the Etruscans around this time also.

|

Edinburgh Painter, Lekythos

showing Theseus and the Minotaur |

There is not much that can be said for the year 503, save that this year the Romans and Sabines fought another war. Nothing can be said to my knowledge for the year 502 but in the year 501 the Romans and Sabines fought once more. This time the Romans were so disturbed at the Sabine attacks that they suspended the normal constitution whereby the consuls would lead the army and they appointed a special official to oversee the state in time of crisis. Unlike the consuls, who were technically equal, this official would, temporarily, be the highest official in the state; one whose decisions could not be overruled. This office was known as “

dictator”, meaning “

one who gives orders” and did not have the negative connotations that it has today. The first dictator known to history was Titus Lartius.

In the year 500 the Olympic Games were held. Nikeas of Opous won the stadion race. Meneptolemos of Apollonia won the boys’ stadion race. The mule cart race was won by Thersios of Thessaly. Philon of Korkyra won the boxing, whereas in the previous Olympics he had been victorious in the boys’ stadion race. Akmatidas of Sparta won the pentathlon. Agametor of Mantineia won the boys’ boxing. Callias of Athens won the tethrippon, meaning that he owned the team of horses that won the chariot race. This Callias is usually referred to as Callias II, because he was the second of this family to bear the name. He was an extremely rich Athenian nobleman, whose wealth came from exploiting some of the silver mines in Laurion in the south of Attica.

|

| Sappho Painter Lekythos |

In the arts, the Edinburgh and Sappho painters flourished around this time. These were vase-painters who both used black-figure but also white-ground technique to paint, what I at least think, are very beautiful vases. The Chiusi Painter and the Sosias Potter also flourished around this time.

In poetry, Asius of Samos flourished around this time, but only a few fragments of his work survive. Acusilaus was a logographer and a mythographer who flourished around this time. A logographer was like an early historian in that he would codify genealogies and myths and try to write down a rational explanation of the world. He may have come from Argos, but it is not clear which Argos (whether in the Peloponnese of Boeotia).

Finally, in the year 500 some exiles from the island of Naxos approached Aristagoras, the tyrant of Miletus seeking aid. They had been driven from their homeland and asked if Aristagoras, with the aid of the powerful Persian Empire, could restore them to their lands. This might seem like a perfectly innocent request and there was nothing out of the ordinary about it. Aristagoras accepted their plea and went to speak to the Persian officials in Sardis about it. Without spoiling anything of what happens in the next few years, suffice it to say that this meeting leads to some very chaotic events.

|

| Coin of Naxos from around 500BC |

When the Naxians came to Miletus, they asked Aristagoras if he could give them enough power to return to their own country. Believing that he would become ruler of Naxos if they were restored to their city with his help and using as a pretext their friendship with Histiaeus, he made them this proposal: “I myself do not have the authority to give you such power as will restore you against the will of the Naxians who hold your city, for I know that the Naxians have eight thousand men that bear shields, and many ships of war. Nevertheless, I will do everything I can to realize your request. This is my plan. Artaphrenes is my friend, and he is not only Hystaspes' son and brother to Darius the king but also governor of all the coastal peoples of Asia. He accordingly has a great army and many ships at his disposal. This man, then, will, I think, do whatever we desire.” Hearing this, the Naxians left the matter for Aristagoras to deal with as best he could, asking him to promise gifts and the costs of the army, for which they themselves would pay since they had great hope that when they should appear off Naxos, the Naxians would obey all their commands. The rest of the islanders, they expected, would do likewise since none of these Cycladic islands was as yet subject to Darius.

Herodotus’ Histories, 5.30, written about 440BC

And thus the period that we are looking at draws to a close. We have seen explorers, philosophers, painters, temple builders, poets, athletes, heroes and villains. We have seen the rise of the Roman Republic and the democracy of Athens. Kings and tyrants have fallen, but the Persian Empire stands as a looming presence to the eastern edge of the Greek world.

|

Red-figure kylix of a woman at an altar,

Attica, circa 510BC |

Primary Sources:

Herodotus’ Histories, written about 440BC

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, written around 400BC

Cicero, Tusculanae Disputationes, written around 45BC

Titus Livius, Ab Urbe Condita, written around 18BC

Polyaenus, Stratagems, written around AD16

Related Blog Posts:

550-525BC in Greece

525-500BC in the Near East

499-490BC in Greece