|

| Fasti Trimphales recording the triumphs of the Republic and early Empire |

The reader should take the dates and the events with a pinch of salt. Dating was an inexact science and there are disagreements on interregnums and other events. Every date in this blog may be incorrect. Most dates for the Roman Republic follow Livy’s dates, which may make the dates somewhat earlier than what they may have actually been. One should also remember that the Roman years fluctuated compared to our own, so an event that I have mentioned as happening in one year may have happened at least partly in the following year.

Also, many of Livy’s sources were the personal histories of the wealthy families of Rome. These were immensely proud and their recollections of their ancestors may be highly fanciful. Some of these records, as we have seen with some of the stories of Tarquin, may in fact have been transposed from Greek history. I will call out these when I can.

|

| Fasti Capitoline, (a copy) showing the consuls of the Republic and early Empire |

The Aequians were raiding Latium once more and Caeso Fabius Vibulanus led an army against them. He waged a short campaign and returned victorious. His colleague was not so fortunate and waged an unsuccessful campaign against the Etruscans of the city of Veii. He found himself in such difficulties he might have been overwhelmed had not the Caeso arrived in time to extricate the beleaguered consul and his army from their difficulties.

After winning his campaign, saving the other consul and returning victoriously to Rome, Caeso Fabius Vibulanus and other members of the Fabii family placed an extraordinary proposal before the people of Rome. Rome faced three enemies at this time: The Aequians, the Volscians and the Veientes. With only two consular magistrates to lead armies, this could lead to problems. The Fabii proposed that they should carry on the war with Veii by themselves. Their private family would fight a full-scale war against one of the wealthiest cities of Etruria. It was an extraordinary proposition and apart from glory, it is hard to know what the Fabii thought they would gain from it. The other Romans accepted this strange proposal and wondered at the courage of the Fabii.

In 478 Lucius Aemilius Mamercus and Gaius Servilius Ahala were elected consuls in Rome. Despite the fact that the Fabii are said to have been waging a private war against Veii, Lucius Aemilius Mamercus led an army against the Veientes and inflicted a defeat upon them. The city of Veii requested a truce which was granted, before being broken by the Veientes (or the Romans) after the consular army had withdrawn. After the truce between Rome and Veii had broken down, the Fabii continued their private war against the Etruscans. Later that year, according to the Fasti Capitolini, Gaius Servilius Ahala died in office and was replaced by Opiter Verginius Tricostus Esquilinus. This is not mentioned by other sources.

|

| A map showing the cities and peoples of central Italy around this time |

The people of Veii were said to be angry at the fact that a single family, albeit a brave, large and well-funded family, should be hemming in their city. They laid a trap for the Fabii clan near the Cremera River, driving cattle through low-lying regions to draw out the Fabii as raiders. The Fabii took the bait and were surrounded and killed to a man. Livy records that 306 of the Fabii clan are said to have died there, effectively wiping out every male member of the family except one young boy who was too young to bear arms.

The Etruscans of Veii then burst past what few defences lay between them and Rome. The cities of Rome and Veii lay very close to each other, within a day’s march in fact. The army of Gaius Horatius Pulvillus, which had been intended to fight the Volscians, was sent against the Etruscans, but suffered a defeat and fell back to the city. The Veientes occupied a position on the Janiculum Hill near Rome and launched raids from there against the city. Rome was not fully under siege, but the enemy now lay within sight of their gates. Sporadic fighting continued throughout the year, with the Romans unable to drive back the Etruscans.

|

| The Fasti showing the list of consuls in the Capitoline Museum |

In the year 476 Aulus Verginius Tricostus Rutilus and Spurius Servilius Structus were elected consuls in Rome. Their first priority was to push back the Etruscans of Veii from their fortified position on the Janiculum. Livy reports that the Etruscans fell into a similar trap that the Fabii had fallen into and were caught in an ambush. The consul Spurius Servilius led his army into a rather dangerous position, but the other consul’s army arrived in time and the Etruscans withdrew from Roman territory.

The tribunes now asked once more for agrarian reform, whereby the poorer people of Rome (meaning the plebeians; definitely not counting non-citizens and slaves) agitated for the lands to be redistributed. The wealthier patrician class had taken most of the lands that Rome had won over the previous centuries and had large estates. The plebeians pointed out that the plebeians were the majority of the soldiers in the army, yet the patricians received the majority of the spoils of war. It is hard to have much sympathy for the patrician cause in modern times. Even in ancient times it was rather hard to justify why one group should have so much more than everyone else. The disputes over land between the patricians and the plebeians would drag on throughout the Republican period and were never fully resolved.

The plebeian tribunes decided to prosecute one of the consuls of the previous year for military incompetence. It was thought that Menenius Lanatus had been close enough to the Fabii at the Cremera that he could have prevented this disaster. The trial was held and the ex-consul was found guilty and fined 2000 asses (or possibly sentenced to death according to one ancient witness).

|

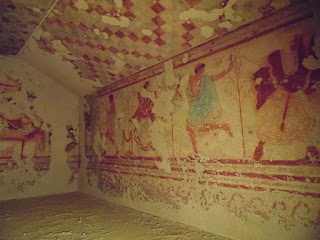

| Etruscan tomb painting from the Tomb of the Tricilinium |

In the year 475 Publius Valerius Poplicola and Gaius Nautius Rutilus were elected consuls in Rome. In this year the ex-consul of the previous year who had nearly lost his army fighting the Veientes was tried for military incompetence. The tribunes of the plebs had brought the charges against the ex-consul, but he disputed these in court and was acquitted.

The consuls raised an army as the war with Veii was ongoing once more and, with the help of the allies from the Hernici, the Romans defeated the Sabines and Veientes near the city of Veii. Publius Valerius Poplicola celebrated a triumph on the first day of the month of May that year. This sounds extremely exact, but the Roman calendar moved around over time so we shouldn’t think it too exact. His colleague had led troops against the Volscians, but with no major engagements.

Elsewhere in Italy, the Messapians defeated the Greeks from the city of Taras. Meanwhile, the Celts had been arriving in northern Italy around this time. According to Livy they were led by a leader called Bellovesus, who defeated the Etruscans at the Ticino River and proceeded to take residence in the rich river lands of northern Italy, founding the settlement that would later become known as Mediolanum and later known as Milan. Livy places this event in the distant past, but it is perhaps more likely that the Celts only began moving into Italy in earnest in the early 5th century, so I have mentioned it here. However, the dates for the battle on the Ticino River must be extremely speculative.

Around this time in Chiusi, an Etruscan tomb was made. Its occupant is unknown, but it is now referred to as the Tomb of the Monkey. It was carved into the tufa rock, possibly in a cross shape; in the shape of what would have been a contemporary Etruscan house. Frescoes adorn the walls and the entire site shows the care that the Etruscans gave to honouring their dead.

In the year 474 Lucius Furius Medullinus and Gnaeus Manlius Vulso were elected consuls in Rome. They mustered armies for further wars against Veii, but the Veientes were clearly tired of war with the ever-energetic Roman Republic. A forty-year truce was given to the Veientes, after the Veientes had promised to supply Rome with money and grain.

Once peace was established in Rome the two consuls faced the demands by the tribunes of the plebs to bring about an agrarian law. The two consuls resisted these demands and the tribunes made no secret of their dislike for the consuls. It was said that in the next year that they would bring the consuls to trial.

|

| Etruscan helmet dedicated by Hiero I of Syracuse after the Battle of Cumae |

In the year 473 Lucius Aemilius Mamercus and Vopiscus Julius Iulus were elected consuls in Rome. The consuls of the previous year were tried by the tribunes of the plebs although the charges were unclear. The patricians were incensed at this and the consuls of the previous year raised a terrible hue and cry about how persecuted they were. To take matters back into their own hands, certain patricians waited until the night before the trial and took it upon themselves to murder one of the tribunes, named Genucius. The patricians were exultant and the plebeians were shocked, as it was a crime against religion to murder a tribune. As a result of the chaos, the charges against the ex-consuls were dropped and the patrician class was riding high.

On the day of the trial the plebeians were in the Forum, on tiptoe with expectation. At first they were filled with amazement because the tribune did not come down; then, when at length his delay began to look suspicious, they supposed he had been frightened away by the nobles, and fell to complaining of his desertion and betrayal of the people's cause; finally, those who had presented themselves at the tribune's vestibule brought back word that he had been found dead in his house. When this report had spread through all the gathering, the crowd, like an army which takes to flight at the fall of its general, melted away on every side. The tribunes were particularly dismayed, for the death of their colleague warned them how utterly ineffectual to protect them were the laws that proclaimed their sanctity.

Titus Livius, Ab Urbe Condita, 2.54, written around 18BC

They then proceeded to try and enlist the plebeians into the army (which would see the people come under the military law of the camp and which gave the consuls the power of life and death over the soldiers). The tribunes did not dare to try and stop this, but one man refused to be sworn into the army as a common soldier, as he had previously been a centurion. The consuls ordered him to be beaten by the lictors, but the refuser, a man named Volero, pushed them away and escaped into the crowd. A riot broke out and the consuls and their lictors had to flee from the fury of the mob. The Senate then met and deliberated on what to do, but the patricians were divided and did not dare risk the further rage of the people.

In 472 Lucius Pinarius Mamercinus Rufus and Publius Furius Medullinus Fusus were elected consuls in Rome. Volero Publilius, the man who had escaped from the lictors and then defied the consuls, was elected as Tribune of the Plebs that year. Volero proposed a new law that would see elections of the Tribunes of the Plebs elected by the Tribal Assembly of Rome, as a way of minimising patrician interference in the elections.

|

| A later European imagining of a Vestal Virgin |

In the year 471 Appius Claudius Sabinus Regillensis and Titus Quinctius Capitolinus Barbatus were elected consuls in Rome. Appius was from a family that was notorious for their hatred of the plebs and his election was probably a means for the patricians to fight against the new proposed law of Volero.

Appius certainly opposed the law and caused a great commotion in the Forum when the discussion of the law was happening. Eventually Appius was removed by his fellow consul, amidst great protests from Appius, as there were riots threatening. The law that Volero had proposed passed and became known as the Lex Publilia.

Later in the year, Appius enrolled an army to fight the Volsci, hoping to win glory for himself in the field, even if the law was passed against his will. The plebeians enrolled in his army hated him so much that they deliberately sabotaged his campaign and his army was defeated in the field. After retreating back to Roman territory he executed anyone who had lost his standards or equipment and then executed one in every ten of those remaining as a collective punishment for their cowardice, which is the first instance recorded of the Roman punishment that became known as decimation. Meanwhile his colleague Titus Quinctius led a successful campaign against the Aequi and returned to Rome acclaimed by patrician and plebeian alike.

In the year 470 Lucius Valerius Potitus and Tiberius Aemilius Mamercinus were elected consuls in Rome. The behaviour of Appius in the previous year had earned him the hatred of the tribunes and he was prosecuted for obstructing the law. Appius relished the struggle and turned his trial into a platform from which to denounce and lambast the tribunes of the plebs. Appius was not condemned however, as he died of natural causes during the proceedings. Livy records that he was mourned by all, but I am quite sceptical of this.

|

| Etruscan tomb painting from the Tomb of the Triclinium |

Elsewhere in Italy, the Etruscan tombs known as the Tomb of the Dead Man (named for a fresco in the tomb rather than its occupant) and the Tomb of the Triclinum were made. These had beautiful frescoes painted on them. It is a pity that so very little is known of Etruscan history. It would be wonderful to have a history of the Etruscans told from the point of view of the Etruscans rather than the Romans, but sadly this is unlikely to ever be found.

In the year 469 Titus Numicius Priscus and Aulus Verginius Tricostus Caeliomontanus were elected consuls in Rome. There were further wars with the Volsci and the Aequi. Reading the history of Livy it would sound as if the wars were interminable, but it must be that the Romans were gradually winning. The two consuls led armies against the Aequi and the Volsci and the port of Antium (the capital of the Volscians) was captured. Meanwhile the Sabines sent a raiding party that pillaged all the way to the gates of Rome while the armies of the consuls were on campaign. However, when the consuls came back to Rome, they pillaged the territory of the Sabines in return.

In the year 468 Titus Quinctius Capitolinus Barbatus and Quintus Servilius Priscus Structus were elected consuls in Rome. Their election seems to have been purely by the patricians, as the plebeians abstained from the consular election in their frustration at being denied the agrarian laws that they had been requesting for decades. However the factional strife between the orders was put on temporary hold while the wars were to be fought.

The Sabines invaded Roman territory in full force after the Roman raids the previous year. The Romans in turn attacked the Sabine lands under the leadership of Quintus Servilius. Both sides did a lot of damage to each other, but no major battles were fought. Titus Quinctius however led his army deep into the territory of the Volsci and after a hard fought series of battles and short sieges, managed to capture Antium. Antium was the largest city of the Volsci and functioned as their capital, probably, but the capture of Antium was not sufficient to destroy the Volsci, although it certainly damaged them. Titus Quinctius returned to Rome and was granted a triumph.

In the year 467 Tiberius Aemilius Mamercinus and Quintus Fabius Vibulanus were elected as consuls in Rome. With the conquest of Antium, the disputes over the agrarian law resurfaced once more and Rome was once more divided. This year however, at least one of the consuls, Tiberius Aemilius Mamercinus, was in favour of an agrarian law of sorts, although his colleague was not. A compromise was reached whereby the people would be granted land at Antium to take for their own. Some opted for this, but many did not, as this land would mean that they would not be able to participate in the affairs of Rome (as they would be too far away). However, the compromise did at least calm things temporarily in Rome. The two consuls raised armies and fought with the Aequi and the Sabines with moderate success.

In the year 466 Quintus Servilius Priscus Structus and Spurius Postumius Albus Regillensis were elected as consuls in Rome. There was a war with the Aequi, but it came to nothing as there was sickness in the Roman camp and the course of the war was handed over to the next consuls.

|

| Goddess statue from Taras (in the Altes Museum in Berlin) |

In the year 465 Quintus Fabius Vibulanus and Titus Quinctius Capitolinus Barbatus were elected as consuls in Rome. They continued the war with the Aequi. The Aequi were entreated to make a peace but they refused. The second consular army joined with the first and the Aequi were brought to battle and defeated. However the Aequi then raided the territory of Latium, but were caught and defeated a second time in the same year.

Elsewhere in Italy around this time, the Etruscan tomb known as the Isis Tomb was built in Vulci. Like the other Etruscan tombs, it contained peaceful scenes of life in frescoes adorning the walls of the underground resting places. I wish that there were other more definite things that could be said about the Etruscans at this time, but the sources are scarce.

In the year 464 Aulus Postumius Albus Regillensis and Spurius Furius Medellinus were elected consuls in Rome. The wars with the Aequi continued and the two consuls led armies to attack their territory. The Aequi attacked the army of Medellinus and the Romans were defeated, with the consular army trapped in its camp. Even the brother of the consul was killed in a sortie and the Aequi were confident in victory. However, another Roman army arrived on the scene and the besieged Romans sallied out of their camp to attack the Aequi. The Aequi were soundly defeated.

In the year 463 Publius Servilius Priscus Structus and Lucius Aebutius Elva were elected as consuls in Rome. That year Livy records strange portents and unusual phenomena, but these were doubtless remembered afterwards because this year saw a pestilence break out in Rome. Many people died; so many in fact, that when an army of Aequi and Volsci descended upon Rome the Romans were unable to even field an army in their defence. Both consuls died from the plague, leaving the city leaderless.

Death had taken Aebutius, the Roman consul; for his colleague Servilius there was little hope, though he still breathed; the disease had attacked most of the leading men, the greater part of the senators, and almost all of military age, so that their numbers were not only insufficient for the expeditions which so alarming a situation called for, but were almost too small for mounting guard.

Titus Livius, Ab Urbe Condita, 3.6, written around 18BC

|

| Etruscan tomb painting from the Tomb of the Triclinium |

In the year 462 Lucius Lucretius Tricipitinus and Titus Veturius Geminus Cicurinus were elected as consuls in Rome. By now the city had mostly recovered from the plague epidemic the previous year. Thus the consuls were determined to punish the invaders of the Aequi and the Volsci for their actions. A successful campaign was waged against the enemies of Rome and Lucius Lucretius Tricipitinus was granted a triumph while his colleague was granted an ovation.

The signs of factional strife were visible again in Rome. One of the tribunes of the plebs, named Terentilius, put forward legislation aimed to limit the power of the consuls, while they were away on campaign. The patricians believed that this was an underhanded tactic and they were not wrong. The motion was deferred to a later time.

In the year 461 Publius Volumnius Amintinus Gallus and Servius Sulpicius Camerinus Cornutus were elected as consuls in Rome. The legislation proposed by the tribune Terentilius, which would see limits placed on consular power, was opposed by the patricians and, unsurprisingly, the consuls. Both the tribunes of the plebs and the consuls had considerable power granted to them in the laws and both sides used these powers to block every action of the other, even going so far as to stop troops being levied to face a foreign threat.

|

| Vase from Etruscan tomb |

The state was nearly paralysed with the conflict between the orders when Livy records that there was a trial ordered for one of the patricians. A young man named Caeso Quinctius, the son of Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, was put on trial for obstructing the tribunes (which he certainly had done) and for murder (which he may or may not have done). He was accused by an ex-tribune of murdering the ex-tribune’s brother.

Rather than facing trial the accused patrician fled the city into exile. The self-imposed sentence of exile was accepted by the tribunes, but his father had to forfeit a large sum of bail money, 3,000 asses (the “as” or “aes” was a Roman coin from a later period). This was enough to bankrupt his father and force the aristocrat to farm his own land himself. Some years later it was reported that the evidence at the trial may have been untrue, but by this time Caeso had died in exile.

|

| Etruscan jewellery |

In the year 460 Publius Valerius Poplicola and Gaius Claudius Sabinus Regillensis were elected as consuls in Rome. The factional strife of the previous years continued. Now rumours grew that there was an aristocratic plot to take over the state and that the exiled Caeso had returned in secret to plot a revolution. The consuls refused to investigate the rumours, believing this to be a trick of the Tribunes of the Plebs to arrest and banish other members of the patrician class.

Meanwhile there was a revolution brewing, just not the one that anyone expected. The victories of the Sabines and other nearby nations had led to a large slave population in Rome. The slaves rose up in the night under the leadership of a Sabine named Appius Herdonius. Some disaffected members of the state, presumably those who had no rights, joined the slave rebellion. They occupied the Capitoline Hill and fortified it against the rest of the city. They were willing to negotiate but also threatened that they would have no issue in negotiating with the enemies of Rome either.

|

| Etruscan bronze metalwork |

Titus Livius, Ab Urbe Condita, 3.15, written around 18BC

The situation was particularly dire in Rome, because the factional strife was now worse than ever. The tribunes believed that the seizure of the Capitol was merely another piece of trickery from the patricians and it seems to have taken many speeches to get the people to actually take up arms against the slaves. To complicate matters an army approached the city and there was consternation as to whether this might be a force of the Aequi or Volsci. It turned out to be a friendly army of the Tusculans, come to aid Rome under the direction of the dictator of Tusculum, Lucius Mamilius.

Once the reinforcements had arrived and the factional strife ceased for a few days, the consuls led an attack on the hill. Publius Valerius Poplicola was slain in the fighting, but the revolt of Herdonius was crushed and the remaining slaves tortured and executed.

The tribunes now wanted to discuss the laws, but the remaining consul refused to have the law discussed until another consul was appointed in the stead of his dead colleague. This had the effect of simply blocking the law for another year.

And thus the time period that we are looking at draws to a close. The factional strife between the plebeians and the patricians, particularly over land reform, continue during this time period. Small continuous wars are fought with the neighbouring tribes, with Rome being victorious more often than not. There are continued tensions with the Etruscans to the north, particularly with the nearby city of Veii. To the south the Greeks fight their wars with the Iapygian speaking tribes, or each other, while to the north the Etruscans build tombs and reach their cultural zenith, sadly rather unknown to us. Further north again the Celts seem to be crossing the Alps and settling in the river plains of northern Italy.

|

| Tomb painting from the Tomb of the Triclinium |

Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, written circa 40BC

Titus Livius, Ab Urbe Condita, written around 18BC

Fasti Triumphales, written circa 19BC

Fasti Capitolini, written circa AD13

Related blog posts:

499-480BC in Rome

489-480BC in Greece

479-470BC in Greece

469-460BC in Greece

479-460BC in the Near East

459-440BC in Rome

No comments:

Post a Comment