|

| Assyrian reliefs from Nineveh |

The Seal of Destinies by which Asshur, king of the gods, seals the destinies the Igigu and Anunnaku gods, the heavens, the netherworld, and mankind. Whatever he seals cannot be changed. Whoever tries change what he seals, may Asshur, king of the gods, and the goddess Mullissu, together with their children, kill him with their mighty weapons. I am Sennacherib, king of Assyria, the ruler who reveres you. Whoever erases my name or alters this Seal of Destinies belonging to you, erase his name and his seed from the land.

The Seal of Sennacherib, RINAP3:212

As is usual for these blogs, a word of caution must be said about our sources and the lack of them. We are fortunate to have a number of Assyrian inscriptions and letters, augmented by some Babylonian chronicles. There are also occasional Egyptian writings and Greek myths to supplement the account, but for this period there are few Hebrew sacred writings that are of interest to the historian. Sadly, unlike the last post on the Near East, we cannot start this post with a talking sheep. As always, the opinions in this blog are my own interpretation of the sources and the events and must be treated accordingly.

|

| Prism of Sennacherib |

In the year 700BC Sennacherib ruled the Assyrian Empire from Nineveh. Shabaka was Pharaoh in Egypt and Nubia. Hezekiah was king of Judah, which had been devastated by the Assyrian invasion from the previous year, which had left Judah as little more than a city-state centred on the untaken city of Jerusalem. Argishti II was king of Urartu, which was still struggling with the aftermath of the Cimmerian invasion and the Assyrian wars of the previous decade. Shutur-Nakhunte II was king of Elam, a strong state in south-western present day Iran, which nevertheless has very few surviving sources.

Just to give context to what was happening elsewhere in the world, the Greeks were founding colonies in the Mediterranean. The Zhou Dynasty in China had moved its capital to Wangcheng around 771 and was now known as the Eastern Zhou as the empire slowly disintegrated into warring states. India was in the Later Vedic Period and the states such as Kuru, Panchala, Kosala and Videha were flourishing along the Ganges Plain. In Mesoamerica the Olmec had abandoned the city at San Lorenzo and the city at the La Venta site was now the focal point of the culture. In Peru the Chavín culture was flourishing near the coastal regions. There were a huge amount of other cultures in Africa and Eurasia as well but these will suffice to give an idea of what was happening elsewhere in the world.

|

| Marshes of southern Mesopotamia |

In the year 700BC there was trouble again in Babylon. The Bit-Yakin tribe of the Chaldeans once again rose up and it seems that Merodach-Baladan once again had a hand in the rebellion. Sennacherib marched into Babylonia and down to the southern marshes where he fought and defeated someone who he calls Suzubu, but whose real name may have been Mushezib-Marduk. Suzubu fled into the marshes and could not be found by the pursuing Assyrians, who by now must have learned to hate the marshes.

I defeated Mushezib-Marduk, a Chaldean who lives in the marshes, at the city Bittutu. As for him, terror of doing battle with me fell upon him and his heart pounded. He fled alone like a lynx and his hiding place could not be found.

Inscriptions of Sennacherib, RINAP3:23

Sennacherib marched further into Chaldea (or Sealand as it was also called), towards the district of Bit-Yakin itself. Merodach-Baladan loaded the gods of his land onto ships and fled down into the Persian Gulf to take refuge in the city of Nagitu in the kingdom of Elam. Sennacherib, frustrated at the mobility of the enemy, who had always managed to elude him in the marshes, burned and destroyed everything that he could on the shores of the marshy sea and marched back to Babylon around the year 699.

|

| Merodach-Baladan II |

…Dislodged the gods of the full extent of his land from their abodes, and loaded them onto boats. He flew away like a bird to the city Nagite-raqqi, which is in the midst of the sea.

Inscriptions of Sennacherib, RINAP3:23

In Babylon, Bel-Ibni, the Babylonian puppet of the Assyrians was found to be unsatisfactory. He had allowed the Chaldeans to revive their strength while Sennacherib was campaigning against Judah and Philistia. He may have even been thought to be in league with the Chaldeans. Sennacherib removed him from the throne and placed his first born son and heir, Ashur-nadin-shumi, on the throne of Babylon. The people of Babylonia had rebelled against Sennacherib and his puppets. Perhaps they would respect his son?

On my return march, I placed Ashur-nadin-shumi, my first-born son whom I raised on my own knee, on his lordly throne and entrusted him with the wide land of Sumer and Akkad.

Inscriptions of Sennacherib, RINAP3:23

Around this time Hezekiah may have made some form of further tributary arrangement with Sennacherib, but this is unknown. In Elam around the year 699, Shutur-Nakhunte II was killed by his brother Hallushu-Inshushinak. The Babylonian Chronicles use the rather strange phrase, “they shut the door in his face” and I am not sure what exactly this means but it is as poetic a phrase as any to describe a coup. Hallushu-Inshushinak assumed the kingship of Elam. The kings of Elam would not have great fortune in this time period.

Shutur-Nakhunte, king of Elam, was seized by his brother, Hallushu-Inshushinak and Hallushu-Inshushinak shut the door in his face.

Babylonian Chronicles: From Nabonassar to Shamash-shuma-ukin

|

| Hakkari Stele |

Around the years 699-697 Sennacherib made an expedition to Mount Nipur, a mountainous region that is not known with certainty by historians and Ukku, a mountainous kingdom that bordered Urartu and was probably the region of Hakkari in present-day Turkey. In 1998 a number of stelae were discovered in Hakkari that are quite interesting and very unlike most other artwork of the Middle East. They appear more closely related to the stelae of the nomadic peoples of the steppes of Central Asia. The stelae were not from this time period however and predate Sennacherib by about 600 years. Sennacherib led the campaign from his chair that was carried into the mountains. He takes care to describe how he went on foot when the path was too steep for the chair to be carried. He pursued the inhabitants of Mount Nipur before turning on Ukku. Maniye the king of Ukku was able to escape, but his city was captured, plundered and destroyed.

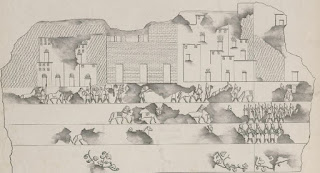

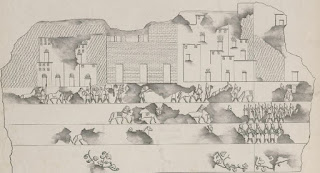

Maniye had probably been a friend of Assyria previously and was probably the source of the report of the Cimmerian invasions of Urartu during the time of Sargon II. So it’s not clear why Ukku was chosen for such destruction. Sennacherib may have wanted to demonstrate Assyrian power on the borders of Urartu. Unlike his father, Sennacherib never fought with Urartu to our knowledge and he may have wanted to have a show of strength on the frontier to make sure that Argishti II did not get any illusions of Assyrian weakness. Stone reliefs of the destruction of Ukku now decorated the walls of Sennacherib’s palace in Nineveh, joining the illustrations of the siege of Lachish.

|

| Mountains of Ukku near Hakkari |

He, Maniye, saw the dust cloud stirred up by the feet of my troops, then he abandoned the city Ukku, his royal city and fled afar

Inscriptions of Sennacherib, RINAP3:23

Around the year 697 it seems that Hezekiah of Judah took his son Manasseh as co-regent. This was not unusual, as the kings of Israel and Judah often seem to have had co-regencies, but Manasseh was probably quite young when he was enthroned, probably just in his teenage years.

In the year 696 there was a rebellion against Assyrian rule in Cilicia. The cities of Hilakku, Ingira and Tarzu (probably Tarsus), rose up, led by the ruler of Illubru named Kirua. The exact map of the campaign is unclear but it seems likely from the records of Sennacherib that the rebels tried to fortify the famous Cilician Gates, one of the few roads through the mountains. The rebellious cities were defeated by Sennacherib’s generals and Kirua was besieged in his city of Illubru, which was reduced by Assyrian siege rams and towers. No ramp was needed to take the city and the walls were broken. The loot and the prisoners were sent back to Sennacherib in the city of Nineveh. The unfortunate Kirua was flayed.

|

| Drawing of the sack of Ukku |

The people living in the cities Ingira and Tarzu aligned themselves with him, then seized the road through the land Que (Cilicia) and blocked its passage.

Inscriptions of Sennacherib, RINAP3:23

The campaign of 696 was a minor footnote and is only mentioned in a few of Sennacherib’s inscriptions. However, the display of Assyrian might must have impressed the Greeks living nearby and they told later legends of an Assyrian king who was buried near Tarsus. When Alexander the Great passed the region many years later on his way to fight Darius at Issus he was shown the “tomb of Sardanapalus”. Some scholars have guessed that this expedition of Sennacherib’s may have given rise to the myth.

Also near the wall of Anchialus was the monument of Sardanapalus, upon the top of which stood the statue of that king with the hands joined to each other just as they are joined for clapping. An inscription had been placed upon it in Assyrian characters, which the Assyrians asserted to be in metre. The meaning which the words expressed was this:—"Sardanapalus, son of Anacyndaraxas, built Anchialus and Tarsus in one day; but do thou, O stranger, eat, drink, and play, since all other human things are not worth this!" referring, as in a riddle, to the empty sound which the hands make in clapping. It was also said that the word translated play had been expressed by a more lewd one in the Assyrian language.

Arrian’s Anabasis Chapter 5, written around 130 AD

In 695 Sennacherib’s generals moved against the border of the Neo-Hittite kingdom of Tabal. Gurdi, the king of the city of Urdutu, was attacked and his city besieged, looted and destroyed, although Gurdi himself was not counted among the slain. Gurdi may have been the king responsible for the death of Sennacherib’s father Sargon, so there may have been motives of vengeance. It may have also been the case that Sennacherib wanted to stay away from the region for superstitious reasons, letting his generals fight these wars.

|

| Mountains of Cilicia |

They besieged that city and took possession of the city by means of piling up earth, bringing up battering rams, and the assault of foot soldiers. They counted the people, as well as the gods, living inside it as booty. They destroyed and devastated that city. They turned it into a mound of ruins.

Inscriptions of Sennacherib, RINAP3:17

However, it was around this time that the Cimmerians were moving into Phrygia and the Assyrians may have wanted to shore up their north-western frontier against the nomadic tribes. Mita of Mushki, who probably was the Midas of Greek legend, had a substantial kingdom in central Anatolia. The Phrygian kingdom goes into decline around this time period and the later classical authors such as Strabo or Jerome record that Gordion was sacked by the Cimmerians and that Midas committed suicide by drinking bull’s blood. The sources here are extremely tentative, as Jerome was writing over a thousand years later and his chronicle is spectacularly wrong on a number of points, but it is likely that the Cimmerians were in the vicinity and that the Assyrians responded as they almost always responded, with a show of force.

|

| Phrygian cauldron |

And those Cimmerians whom they also call Trerans (or some tribe or other of the Cimmerians) often overran the countries on the right of the Pontus and those adjacent to them, at one time having invaded Paphlagonia, and at another time Phrygia even, at which time Midas drank bull's blood, they say, and thus went to his doom.

Strabo 1:3:21, writing around 24AD

In 694 Sennacherib decided to move against the Chaldeans who had fled across the sea to Elam. He did so in a way that was characteristically megalomaniacal, elaborate and intelligent. He had previously cemented his rule over Phoenicia and imposed some form of sovereignty over Cyprus. The Assyrians themselves were not noted sailors, but the Phoenicians and the Greeks were. Sennacherib ordered them to build sea-going ships on the Tigris River and then sailed them down as far as the city of Opis, on the northern frontier of Babylonia. Because the Chaldean tribes must have controlled the mouths of the Tigris River, Sennacherib then had the ships transported on rollers and then into the canal systems of Babylon before sailing them down the Euphrates River, with Sennacherib and the armies following by land.

|

| Nineveh relief of Assyrian ships |

They skilfully built magnificent ships, a product characteristic of their land. I gave orders to sailors of the cities Tyre and Sidon, and the land Ionia, whom I had captured. My troops let the sailors sail down the Tigris River with them downstream to the city Opis. Then, from the city Opis, they lifted the boats up onto dry land and dragged them on rollers to Sippar and guided them into the Araḫtu canal, where they let them sail downstream to the canal of Bit-Dakkuri, which is in Chaldea.

Inscriptions of Sennacherib, RINAP3:46

They arrived at the marshlands near the edge of the sea and apparently pitched their camp miles from the sea. However this was still too close and the camp had problems with the tides. The Phoenician and Greek sailors probably had real difficulties with the tides. Their ships were built for the Mediterranean, which only experiences very minimal tides. Their boats must also have had very low draughts to allow them to sail along the canals. So they may have had to refit them to sail in the Persian Gulf. The records of Sennacherib say that they spent five days and nights waiting for the tides to abate before Sennacherib offered sacrifices and the ships laden with warriors set off.

For five days and nights, on account of the strong water, all of my soldiers had to sit curled up as though they were in cages.

Inscriptions of Sennacherib, RINAP3:46

It cannot have been the full army, as it seems to suggest that Sennacherib stayed on dry land the entire campaign. The Assyrian navy landed at Nagitu and surprised the Elamites and Chaldeans, capturing their gods and taking prisoners before burning what they could not carry and returning across the sea to their waiting king. Sennacherib had taken a huge risk with entrusting his soldiers to the sea and it had paid off, except that it hadn’t.

|

| Mesopotamian marshes |

My warriors reached the quay of the harbour and like locusts they swarmed out of the boats onto the shore against them and defeated them. … They carried off their garrisons, the population of Chaldea, the gods of all of the land Bit-Yakin. … They destroyed, devastated, and burned with fire those cities. They poured out deathly silence over the wide land of Elam.

Inscriptions of Sennacherib, RINAP3:46

Hallushu-Inshushinak, king of Elam, must have heard word of the preparations and guessed what it was for. While Sennacherib carried out his convoluted plan of striking from the southern edge of Mesopotamia, the Elamites carried out a very simple plan attacked Babylonia on the usual land route during his absence, outflanking the Assyrian army and cutting their supply lines. Sennacherib had won a victory to be sure but his army was now in a very dangerous position. Sippar, a sacred city that was an Assyrian base in the region, was captured by the Elamites and its inhabitants slaughtered. The Elamites then moved on Babylon where the inhabitants of the city, hating Sennacherib and all associated with him, took his son prisoner. Ashur-nadin-shumi was the crown prince of Assyria and king of Babylon so this was the most serious of rebellions against the Assyrians. Ashur-nadin-shumi was handed over to the Elamites, transported to Elam and presumably executed. There is no record of any attempts to use him as a hostage. Sennacherib was probably not in a mood to bargain.

|

| Assyrians transporting prisoners |

Afterwards, Hallushu-Inshushinak, king of Elam marched to Akkad and entered Sippar at the end of the month Tashritu. He slaughtered its inhabitants. Shamash did not go out of Ebabbar. Ashur-nadin-shumi was taken prisoner and transported to Elam.

Babylonian Chronicles: From Nabonassar to Shamash-shuma-ukin

In 693, while the fighting continued, the Elamites put Nergal-ushezib on the throne of Babylon and he promptly attacked Nippur, another sacred city that was loyal to the Assyrians. The Assyrians moved north and took Uruk, slaying as they went. The Elamites seem to have moved south to attack the Assyrians but end up just attacking Uruk, which had the misfortune to be sacked twice in a few months. Nergal-ushezib tried to stop Sennacherib at Nippur in a battle that the Assyrians had to win in order to return home. The Chaldeans and Babylonians were no match for the Assyrians and Sennacherib captured Nergal-ushezib and brought him back to Nineveh, where he was imprisoned and died in captivity.

On my return march, in a pitched battle, I defeated Nergal-ushezib, a citizen of Babylon who had taken the lordship of the land of Sumer and Akkad for himself during the confusion in the land. I captured him alive, bound him with tethering ropes and iron fetters, and brought him to Assyria

Inscriptions of Sennacherib, RINAP3:23

Assyria went on the attack again, capturing border cities between Assyria and Elam. The Elamites fell back to one of their capitals, Madaktu, in the Iranian mountains, while Sennacherib pursued them vengefully. The Elamites were unable to take the strain of the war and Hallushu-Inshushinak was murdered by his own people and his son Kutir-Nakhunte III succeeded him on the throne. It should be noted that the Babylonian records suggest that Hallusu-Inshushinak was murdered before Sennacherib started his campaign. However, Sennacherib’s forces were now overstretched and too far from home. The Assyrian records speak of the armies facing severe cold and heavy rainstorms in the mountains as they pushed towards the capital. Rather than risking his armies Sennacherib retreated. The story of the extreme cold may have been an excuse, as now a Chaldean called Mushezib-Marduk had declared himself king of Babylon and the Assyrians were fully committed in Elam and unable to deal with the new threat.

I ordered the march to the city Madaktu, his royal city. In the month Tamḫīru, bitter cold set in and a severe rainstorm sent down its rain. I was afraid of the rain and snow in the gorges, the outflows of the mountains.

Inscriptions of Sennacherib, RINAP3:23

In the year 692 Kutir-Nakhunte III of Elam was murdered by his brother Humban-Nimena III who seized the throne for himself. Sennacherib viewed this as the act of the god Asshur fighting his battles for him and his scribes wrote about the murder glowingly in the records.

Kutir-Nakhunte, king of Elam, was taken prisoner in a rebellion and killed. For ten months Kutir-Nakhunte ruled Elam. Humban-Nimena in Elam ascended the throne.

Babylonian Chronicles: From Nabonassar to Shamash-shuma-ukin

In the year 691 there is not much to record. Presumably Assyria, Babylonia and Elam were all resting their forces and preparing for the next inevitable war.

|

| Statue of a god with Taharqa's features |

In 690 our gaze shifts temporarily to Egypt. Shabaka, Pharaoh of Egypt, who had ruled probably since 705. He had been a strong ruler and had ruled both Egypt and Nubia. However, there are some suggestions that Shabaka’s death may have had political intrigue surrounding it. Taharqa, who was either Shabaka’s brother or nephew took the throne rather than Shabaka’s son Tantamani. Also, in Taharqa’s inscriptions describing his rise to power Taharqa never mentions Shabaka, instead stressing that Shebitku, a previous Pharaoh, favoured him more than Shebitku’s children. However, I am not convinced that Taharqa was a usurper. He left Shabaka’s son Tantamani alive and Tantamani succeeded him on the throne when Taharqa died later. With so many rulers being overthrown in this period it may be that historians see conspiracies behind every change of rulers.

Shabaka had left a number of inscriptions cementing his power in Lower Egypt and when he died he was placed in an impressive pyramid in the royal cemetery of El-Kurru near his brothers Piye and Shebitku and his father Kashta. Shabaka’s armies had not been successful in stopping the Assyrians in their attack on Philistia and Judah, but the Egyptian state that Taharqa inherited was still one of the strongest states in the region. Taharqa had probably been the general who led the force that attacked the Assyrians and would have been acutely aware of the Assyrian threat to the north and east.

|

| Shabaka Stone |

This writing was copied out anew by his majesty in the house of his father Ptah-South-of-his-Wall, for his majesty found it to be a work of the ancestors which was worm-eaten, so that it could not be understood from the beginning to end. His majesty copied it anew so that it became better than it had been before, in order that his name might endure and his monument last in the House of his father Ptah-South-of-his-Wall throughout eternity, as a work done by the son of Re (Shabaka) for his father Ptah-Tatenen, so that he might live forever.

Shabaka Stone

In the same year 690 the war between Assyria, Babylon and Elam flared up again. Sennacherib marched on Babylonia, as the Babylonians sent a plea for help to the new Elamite king Humban-Numena III. The Elamites had suffered greatly in previous years of war so to ensure that the Elamites came, Mushezib-Marduk took the treasures of the great shrine of Babylon, the Esagila, and sent them to the Elamites. Humban-Numena took the bribe and began to gather his allies, confederates and tributaries for war. The Elamites marched with not only their own army but the Chaldeans, Arameans, and what the Assyrian writers describe as the “

lands of Parsuas, Anzan, Pasheru and Ellipi”. This is one of the indications that the Indo-European tribe known as the Persians (Parsuas) had moved southwards to the vicinity of Elam at this time. If the Persians were indeed marching to battle then one of their chiefs may have been Achaemenes, the legendary ancestor of the later rulers of the Persian Empire. He may or may not have existed but if he did exist, it is likely that he was in the Elamite host. Despite the later power of the Persians, at this point they were merely an allied tribe of the Elamites.

They opened the treasury of Esagila and took out the gold and silver of the god Marduk and the goddess Zarpanitu, the property of the temple of their gods. They sent it as a bribe to Humban-Numena, the king of the land Elam, who does not have sense or insight, saying: “Gather your army, muster your forces, hurry to Babylon, and align yourself with us! Let us put our trust in you.

Inscriptions of Sennacherib, RINAP3:23

The Babylonians and the Elamites joined forces and marched towards the city of Halule. On the plains of Halule the armies of the Elamites, Babylonians, Chaldeans and their allies did battle with the Assyrians. The scribes of Sennacherib write about it in breathless detail, possibly the most lurid description of any Assyrian battle. The Elamites were drawn up on the banks of Tigris and Sennacherib’s forces were unable to reach the water, so it was probably the Assyrians who attacked to try and force their enemies away from the river. As with nearly all ancient battles we have no idea of tactics, all we hear about are the fantastic and improbable exploits of the king, told in ever more gory detail. The slaughter continued into the night when the Assyrians finally stopped killing.

|

| Assyrian Lachish relief from Nineveh |

Like a spring invasion of a swarm of locusts, they were advancing towards me as a group to do battle. The dust of their feet covered the wide heavens like a heavy cloud in the deep of winter. … Like a flood in full spate after the storm, I made their blood flow over the broad earth. The swift thoroughbreds harnessed to my chariot plunged into rivers of their blood.

Inscriptions of Sennacherib, RINAP3:23

Sennacherib records a complete victory for the Assyrians. The kings of Babylon and Elam are described as fleeing from the battlefield while defecating in their chariots from sheer terror. The herald of the Elamites is mentioned among the slain and a son of the wily Merodach-Baladan was captured alive by the Assyrians. Sennacherib mentions that he spilled blood like a river and that his chariot wheels were bathed in gore. In another inscription he mentions that he killed one hundred and fifty thousand of their combat troops.

The other records tell a more nuanced and contradictory story. Like the campaign against Philistia and Judah, the bombastic language about Halule may be used to mask the fact that something had gone wrong. The Assyrians may well have held the field, killed some high-ranking Elamites and captured high profile prisoners. But they must have done so at a terrible price. The Babylonian records bluntly state that the Elamites forced Sennacherib to retreat. Sennacherib’s list of enemy casualties is far too high to be plausible. According to Sennacherib, the Elamite/Babylonian casualties were three times higher than the British casualties on the first day of the Somme, which is … unlikely.

|

| Iranian seal |

Humban-nimena mustered the troops of Elam and Akkad and he did battle against Assyria in Halule. He effected an Assyrian retreat.

Babylonian Chronicles: From Nabonassar to Shamash-shuma-ukin

What is most likely to have happened is that the two armies clashed in a close-fought struggle before breaking off from combat once night had fallen. During the night the Babylonians and Elamites retreated and the Assyrians retreated over the next few days. For all Sennacherib’s claims of victory, his army was in no fit state to pursue or to commence sieges. The great battle left all three kings alive and on their thrones and Sennacherib now needed to use propaganda to show how the bloody stalemate and strategic defeat was in fact a great personal victory. It is a useful warning against relying entirely on Assyrian sources.

The armies of all three states must have been heavily damaged, but the Assyrians were damaged the least and later that year they seem to have been involved in a campaign against the oasis city of Dumatha in present-day Saudi-Arabia, where they were engaged in battle with yet another queen of the (possibly) matriarchal Arabs. The city they attacked was known as Adummatu to the Assyrians, Dumatha to the Romans and Dumat al-Jandal to the Arabs. It contained a shrine to the goddess of the morning star, Atarsamain, and was the main city of the Kedarite Arab tribe in the region. It is unclear why it was attacked by Sennacherib, but it is likely that this expedition was undertaken by a different, smaller army, rather than the main army which had suffered at Halule. Some scholars place this campaign several years later however.

I carried off Teʾelḫunu, queen of the Arabs, together with her gods

Inscriptions of Sennacherib, RINAP3:35

The year 689 saw the Assyrians powerful, yet fearful after their reverse at Halule, wanting to take revenge on their enemies but not wanting to risk another full-blown confrontation. Of the organised empires of the Near East, only the Egyptians, the Elamites and the Urartians were really capable of fielding an army against them in the field. Then suddenly, without warning or expectation, the game was changed. Humban-Numena III of Elam was stricken with a paralysis that affected him so badly that he was unable to speak. Sennacherib mustered his armies, knowing that his chief rival in the wars to the south was powerless to take the field against him. It would have been better for the Babylonians and the Elamites if Humban-Numena III had actually passed away but the paralysed king could neither command his armies in person nor order his generals into the field.

On the fifteenth day of the month Nisannu, Humban-nimena, king of Elam, was stricken by paralysis and his mouth was so affected that he could not speak.

Babylonian Chronicles: From Nabonassar to Shamash-shuma-ukin

Within a few months Sennacherib must have brought his armies southwards and towards Babylonia. We have no details of the siege but the Babylonian chronicles record that around seven months after the paralysis of the Elamite king, that Babylon had fallen. Sennacherib captured Mushezib-Marduk and had him sent in captivity to Assyria where his fate is unlikely to have been pleasant.

Sennacherib had ignored the traditional rites of the Babylonians, never having undertaken their ceremonies of kingship, as his predecessors Tiglath-Pileser III and Sargon II had done. He had simply assumed the kingship as his right through force of arms and the later Babylonian chronicles record his early years as kingless. He had installed a Babylonian lackey as king before placing his son on the throne. The near continuous rebellions and the betrayal of his son to the Elamites showed the Babylonian response to Sennacherib’s contempt. When they handed Ashur-nadin-shumi to the Elamites the Babylonians had sealed the prince's fate as surely as if they had murdered him themselves. Faced with the simmering resentment Sennacherib decided to take a drastic step. He destroyed Babylon.

|

| Assyrians transporting prisoners |

I destroyed, devastated, and burned with fire the city, and its buildings, from its foundations to its crenellations. I removed bricks and earth, as much as there was, from the inner and outer walls, the temples, and the ziggurat, and I threw into the Araḫtu River. I dug a canal into the centre of that city and leveled their site with water. I destroyed the outline of its foundations and made its destruction surpass that of the Deluge. So that in the future, the site of that city and temples will be unrecognizable. I dissolved Babylon in water and annihilated it, making it like a meadow.

Inscriptions of Sennacherib, RINAP3:24

This was a horrendous crime in the eyes of the Assyrians. Babylon was a sacred city, not just to a foreign god, like Jerusalem, Adumattu or Musashir, but to Marduk, a god within their own religion. Sennacherib attempted to justify his actions by referencing some sacrileges of the Babylonians against the city of Ekallatum committed 418 years prior. But then he boasted of the level of destruction, comparing his actions to the Deluge that destroyed all mankind in early history and boasting of diverting canals into the city so as to ensure that the floodwaters of the rivers would erase the troublesome city forever. Those who were not killed were deported and Sennacherib hoped that the city would never rise again. The wars between the Assyrians and Babylonians seemed to have been finished forever. It is worth noting that many key details of this attack, siege and capture are missing and that the destruction that Sennacherib accomplished was probably less than he intended. Daesh have attempted to destroy many relics of cities in the region, including some of Sennacherib’s own. But even with modern explosives it is quite difficult to erase all traces of a city. Babylon would not rise again in Sennacherib’s lifetime, but it would rise again.

Later in the year 689 Sennacherib made another controversial decision. His eldest son, Ashur-nadin-shumi, had been murdered by the Babylonians. He now needed a new crown prince and he now designated a younger son, Esarhaddon, as crown prince. Please note that the dates here are unclear and this may have in fact happened in 683. Esarhaddon was the son of Sennacherib’s favourite queen, Naqia, or Zakutu as she is also known, and this probably influenced the decision. The other, older, sons of Sennacherib were furious at being passed over, with Arda-Mulisshi and Nabu-sharra-usur particularly being angry. Esarhaddon seems to have suffered from health problems and was seen as a weak choice, so Sennacherib made the Assyrian generals and leaders swear an oath of loyalty to the new crown prince.

|

| Assyrian Lachish relief showing Sennacherib |

Before the gods Asshur, Sin, Shamash, Nabu, and Marduk, the gods of Assyria, the gods who live in heaven and netherworld, he made them swear their solemn oaths concerning the safe-guarding of my succession.

Inscriptions of Esarhaddon: RINAP4:1

Also around this time the Assyrians seem to have established some form of diplomatic relations with the kingdom of Saba in what is now Yemen. There are a number of small inscriptions from Nineveh bearing the name of Karibi-ilu. This has been suggested to have been the king Karib’il Watar, a great conqueror in the kingdom of Yemen. However, Karib’il Watar is probably later, perhaps by a few hundred years. It is possible that it was an earlier Mukarrib of Saba, Karab-El Bayin, who was the Sabaean king mentioned by the Assyrians. It is possible that this connection was sought by the Arabs of southern Arabia wanting to establish good relations with the Assyrians, who controlled the northern edges of their trade routes. Possibly the conquest of the Arabian city of Adummatu had got their attention, or possibly the fact that the inhabitants of Dilmun (probably present-day Bahrain) seem to have had some dealings with the Assyrians around the time of the fall of Babylon in this year. Whatever the truth or otherwise of these conjectures it is a good reminder of the interconnectedness of the ancient world, even in times of war.

The audience gift that Karib-il, king of the land Saba, presented to me. Whoever places it in the service of a god or another person or erases my inscribed name, may the deities Asshur, [...], Sin, and Shamash make his name and his seed disappear.

Inscriptions of Sennacherib, RINAP3:24

In 688 Humban-Numena III finally died of his paralysis, which was probably caused by a stroke, and his son Humban-Haltas I succeeded him. There is not much more that can be said of the year 688, as the records of the Assyrians are silent for this time.

On the seventh day of the month Addaru Humban-nimena, king of Elam, died

Babylonian Chronicles: From Nabonassar to Shamash-shuma-ukin

Around the year 687 Hezekiah, king of Judah, dies. He was succeeded by his son and co-ruler Manasseh. The dynasty of Judah appears to have had relatively few coups and their custom of installing the crown prince as co-ruler while the king was still alive appears to have been a very successful one. While Hezekiah is remembered as a good ruler by the later sacred writings of the Hebrews, the kingdom that Manasseh inherited was a shadow of its former self. Judah was reduced to a paltry city state, with all but its capital in disarray, so Manasseh reversed most of the decisions of his father. He seems to have been quite pro-Assyrian, with one possible exception, and certainly paid tribute to the Assyrian kings. He also reversed the decision to centralise worship in Jerusalem, allowing the local cults in the countryside to flourish. He may have tried to foster trade as well in the region. Apart from damning his reversal of Hezekiah’s reforms, the Biblical Book of Kings says very little about his long reign so we must rely on archaeology, which appears to show that there was a revival of Judah’s economy during this time.

|

| Statue of Baal |

Manasseh was twelve years old when he began to reign, and reigned fifty and five years in Jerusalem. And his mother's name was Hephzibah. And he did that which was evil in the sight of the Lord, after the abominations of the heathen, whom the Lord cast out before the children of Israel. For he built up again the high places which Hezekiah his father had destroyed; and he reared up altars for Baal, and made a grove, as did Ahab king of Israel; and worshipped all the host of heaven, and served them. And he built altars in the house of the Lord, of which the Lord said, In Jerusalem will I put my name. And he built altars for all the host of heaven in the two courts of the house of the Lord. And he made his son pass through the fire, and observed times, and used enchantments, and dealt with familiar spirits and wizards: he wrought much wickedness in the sight of the Lord, to provoke him to anger.

2 Kings 21:1-6

Even with Manasseh’s recovery the kingdom of Judah was now probably weaker than the surrounding kingdoms of Ammon and Moab and large sections of it were ruled by the Philistines. Manasseh’s reforms and hostility to his father’s advisors probably influences the silence of the sources. Later traditions record that he executed the prophet Isaiah, using the fairly dreadful method of sawing him in half and there are no prophets said to be active during his reign. During the first few years of Manasseh’s rule the southern Levant (Philistia/Judah/Moab/etc.) seems to have come under the influence of the Egyptian Pharaoh Taharqa. Taharqa was interested in the region and Sennacherib seems to have not led any more campaigns in the area after this conquest of Babylon.

Isaiah said to himself: I know him, i.e., Manasseh, that he will not accept whatever explanation that I will say to him to resolve my prophecies with the words of the Torah. And even if I say it to him, I will make him into an intentional transgressor since he will kill me anyway. Therefore, in order to escape, he uttered a divine name and was swallowed within a cedar tree. Manasseh’s servants brought the cedar tree and sawed through it in order to kill him. When the saw reached to where his mouth was, Isaiah died.

Yevamot 49b:8, written around 500AD

|

| Remains of Sennacherib's aqueducts |

From 689 to 681 the Assyrian sources become nearly silent. To some extent this is because the early stages of a king’s rule are generally better documented than the later years. But it does also seem that Sennacherib did not do any major campaigns for these years. Doubtless there were small campaigns, but there is no fully satisfactory explanation for why Sennacherib did not go to war. Most of his enemies were defeated to be sure, but the Assyrian armies were usually at war. Some have hypothesised a second campaign to Judah during this time period but, while not impossible, there are good reasons to suspect that this was not the case.

It is as good a time as any to speak of Sennacherib’s building projects. Like his father, Sennacherib was a prolific builder, demanding that his captives and subject kings provide him with labour and raw materials to make Nineveh the finest city in the world. During the first fifteen years of his rule he had built up new palaces, changed the courses of rivers, re-walled his cities, dedicated and rebuilt temples old and new and built a massive canal and aqueduct system to supply his capital and its gardens with water. To water the high terraced gardens the Assyrians used what is almost certainly an Archimedes screw and Sennacherib claims to have invented new methods of bronze casting and transportation for his statues of bronze and stone. When Babylon was destroyed Nineveh was most probably the largest city on earth.

|

| Assyrian relief of irrigated gardens |

I planted alongside the palace a botanical garden, a replica of Mount Amanus, which has all kinds of aromatic plants and fruit trees, trees that are the mainstay of the mountains and Chaldea, collected inside it.

Inscriptions of Sennacherib, RINAP3:46

There has never been a trace of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon found in the ruins of Babylon. However, Stephanie Dalley, an archaeologist who has worked extensively in the region believes that the palace gardens of Sennacherib were what founded the legend. Possibly the gardens were in fact in Babylon or possibly they never existed. But it is also possible that Sennacherib had created one of the wonders of the world.

I have set eyes on the wall of lofty Babylon on which is a road for chariots, and the statue of Zeus bv the banks of the Alpheus, and the hanging gardens, and the colossus of the Sun, and the huge labour of the high pyramids, and the vast tomb of Mausolus…

Antipater of Sidon, writing around 140BC

In 689 Sennacherib had made Esarhaddon crown prince of the Assyrian Empire, which had enraged the older sons of Sennacherib who had been passed over in the line of succession. These had continued to plot and scheme against the sickly youngster and it seems that around 683 Esarhaddon had had to flee to the land near Harran in present day Syria, because the plots against him were too much. His mother Naqia probably had a hand in sending her son to safety.

By the command of the great gods, my lords, the gods settled me in a secret place away from the evil deeds, stretched out their pleasant protection over me, and kept me safe for exercising kingship.

Inscriptions of Esarhaddon: RINAP4:1

The other princes had their followers who wanted to see them gain power and the sacrilegious sacking of Babylon would have made Sennacherib very unpopular with his own people and army. In 681 the conspirators struck. Sennacherib was surprised in his palace and stabbed to death. At least two princes who were in Nineveh took control of the army and sent a force swiftly westwards to deal with the exiled crown prince. However Esarhaddon had heard the news and was rushing back towards Nineveh to claim the throne himself. The generals had sworn oaths to support him and these oaths held. The troops sent to slay Esarhaddon joined his forces instead and the young prince marched on Nineveh. His brothers fled northwards towards Urartu.

|

| Medieval manuscript showing death of Sennacherib |

Afterwards, my brothers went out of their minds and did everything that is displeasing to the gods and mankind, and they plotted evil, girt their weapons, and in Nineveh, without the gods, they butted each other like young goats for the right to exercise kingship. … I did not hesitate one day or two days. … With difficulty and haste, I followed the road to Nineveh and before my arrival in the territory of the land Ḫanigalbat all of their crack troops blocked my advance … In their assembly, they said thus: ‘This is our king!’ Through Ishtar’s sublime command they began coming over to my side and marching behind me.

Inscriptions of Esarhaddon: RINAP4:1

There has been some suspicion that Esarhaddon conspired against his father and had him murdered. After all, Esarhaddon was the one who eventually benefitted the most from the murder. But there are strong indications that Esarhaddon’s account of his brothers murdering the king and Esarhaddon marching to the rescue are in fact correct. The Babylonian chronicles record simply that “a son” of Sennacherib’s slew him. The Bible records that he was murdered by “Adrammelech and Sharezer”, while Berossus, a Babylonian writer from the Classical period, records that “

a trap was readied for him by his son Ardumuzan…” Adrammelech and Ardumuzan probably refer to the prince Arda-Mulisshi while Sharezer probably refers to Nabu-sharra-usur.

And it came to pass, as he was worshipping in the house of Nisroch his god, that Adrammelech and Sharezer his sons smote him with the sword: and they escaped into the land of Armenia. And Esarhaddon his son reigned in his stead.

2 Kings 19:37 KJV, written around 550BC

|

| Modern illustration of the flight of Adrammelech |

To clinch the argument, a letter from Babylonia was found that describes the acts preceding the murder, where an official discovered the plot and was veiled and taken to see the king. The hooded official was taken into the presence of the king and revealed what he knew of the conspiracy. The hood was then taken off the head of the hapless official who found that he had been taken to see the rebellious princes instead of the king. The princes then interrogate and murder the official and any others who had already been told. The text then breaks off. It would seem that all the sources confirm Esarhaddon’s story and in the words of Parpola we may “

acquit the harassed king of the murder charge he does not deserve and convict the man to whom all the evidence points…”

681 was obviously a bad year for kings. Not only was Sennacherib murdered by his sons but the king of Elam, Humban-Haltas I, developed a sudden paralysis and died at sunset on the same day. Presumably this was a stroke, like the one that had killed his father. The possibility of some genetic disorder is certainly worth considering here. His son, Humban-Haltas II, succeeded him. There is a note in the Babylonian chronicles about gods of Uruk returning to their city from Elam so it is possible that the Elamite king was normalising relations with Sennacherib before both of them died.

On the twenty-third day of the month Tashritu, at the noon hour, Humban-Haltash, king of Elam became paralyzed and died at sunset.

Babylonian Chronicles: From Nabonassar to Shamash-shuma-ukin

It’s probably worth saying a few words about Sennacherib. It’s hard to write a history of these times that does not end up becoming a biography of the Assyrian kings. Sennacherib was a capable and ruthless king and commander. He was cruel, but probably not much more so than most of the kings of Assyria. He was a great builder, with the city of Nineveh standing as his monument but also a destroyer of many cities, particularly Babylon. Some have seen him as almost an atheist who feared no retribution from the gods. This is probably false. While we know much of Sennacherib, everything that we know comes from his enemies or his scribes. Like most rulers of the ancient world he was probably illiterate so no writings of his have come down to us, and we can only speculate on his actual thoughts, fears and beliefs.

Palace of Rest, an eternal dwelling, the firmly-founded family house of Sennacherib, great king, strong king, king of the world, king of Assyria.

Tomb Inscription from Nineveh: RINAP3:203

|

Gustave Dore's print of the

Destruction of Sennacherib |

He is remembered from the writings of his enemies in Babylon and Judah and in later times may have partly inspired some of the legends of the Greeks. In later millennia he inspired the famous poem of Lord Byron. However one of the most intriguing memories of Sennacherib is preserved in the Talmud. Here there is a tale of two Pharisees Shemaiah and Avtalyon, who are described as descendants of Sennacherib. They were both major figures in Judaism around 100BC. Shemaiah was Nasi (meaning “Prince”) of the Sanhedrin. Both were teachers of Hillel, one of the most important rabbis in the history of Judaism. It seems that it was important for those the descendants of the enemies of Sennacherib to believe that not only had the Assyrian attacks against them failed, but that even his descendants had now joined them.

In 680 Argishti II of Urartu died and was succeeded by his son Rusa II. In Babylonia, the son of Merodach-Baladan, Nabu-zer-kitti-lisir, revolted against the Assyrians and attacked Ur. However, the Chaldean attack failed and he had to flee to Elam. The Elamites had no desire to restart the wars with Assyria so rather than granting Nabu-zer-kitti-lisir asylum, they killed him. Chaldea was then ruled by his brother Na’id-Marduk, who made immediate submission to Esarhaddon.

Another Chaldean tribe, the Bit-Dakkuri, were also crushed at this time, with their king Samas-ibni taken prisoner and another prominent Chaldean, Nabu-shallim, made ruler of the Bit-Dakkuri. Yet another Chaldean tribe of the marshlands, the Gambulu, made peace with Assyria and were instated as a defence against Elam. The campaigns of Esarhaddon are not arranged chronologically like other Assyrian kings and it can be a little difficult to ascertain what happened when. But it is most likely that the wars against the Bit-Yakin, Bit-Dakkuri and Gamulu all happened in or around 680.

|

| Esarhaddon |

At that time, Nabu-zer-kitti-lisir, son of Merodach-baladan, governor of the Sealand, who did not keep his treaty nor remember the agreement of Assyria, … I sent my officials, the governors on the border of his land, against him. … The rebel, the traitor, heard of the approach of my army and fled like a fox to the land Elam. Because of the oath of the great gods which he had transgressed … they killed him with the sword in the midst of the land Elam.

Inscription of Esarhaddon, RINAP 4:1

Around this time a document seems to have been composed by the Assyrian scribes in Nineveh called the Sin of Sargon. It is written as if it was document of Sennacherib’s, where he is wondering for what sin his father, Sargon II, was slain. After much soul-searching and enquiry to the gods he finds out that Sargon had not treated the gods of Assyria and Babylonia correctly. The gods require new statues of both Assur and Marduk to be made and if these were not made then it would spell disaster for the king. Then Sennacherib reveals that he is speaking from beyond the grave and that he had been unable to create the new statue of Marduk and that for this sin he was slain. It is a rather intriguing text but it shows that the new king Esarhaddon had determined to avoid the fates of his father and grandfather and was planning to restore Babylon.

As for me (Sennacherib), after I had made the statue of Assur my lord, Assyrian scribes wrongfully prevented me from working on the statue of Marduk and did not let me make the statue of Marduk, the great lord, and thus shortened my life.

The Sin of Sargon

|

| Drawing of Assyrian relief of building a palace |

The Cimmerian threat to the north had not gone away and it seems that the kingdom of Phrygia had been wiped out around this time. The Assyrian empire must have been a tempting target and the Neo-Hittite states near Cilicia and the Taurus mountains were always quite rebellious against the Assyrians. The Assyrians had to respond to the threat and their armies moved to the north-east to face the Cimmerians. The mobile horse tribes of the Cimmerians would have been a real threat to the less mobile Assyrians, so there seems to have been a temporary alliance with the Scythians. The Scythians were another horse tribe from the north, closely related to the Cimmerians and the Medes, and their mobility combined with Assyrian strength would enable the Cimmerians to be halted. But Esarhaddon was unsure if these horse raiders from the steppes could be trusted and we know that he consulted the gods and oracles to see if they would keep their word. The temporary alliance worked and the Cimmerians under their lord Teushpa (possibly a similar name to the Persian name Teispes) were halted and the Cilician cities around Tabal were plundered.

Moreover, I struck with the sword Teushpa, a Cimmerian, a barbarian whose home is remote, together with his entire army, in the territory of the land Ḫubushna.

Inscription of Esarhaddon, RINAP 4:1

While the Assyrians were facing the northern threat of the Cimmerians another threat emerged. The king of Sidon, Abdi-Milkutti, formed an alliance with two small states (Kundi and Sissu) in Cilicia and rebelled. Possibly the plans were afoot before the defeat of the Cimmerians. The Phoenicians of Sidon were almost certainly supported by Taharqa, Pharaoh of Nubia and Egypt. The Assyrian army in the north seems to have split into two groups, one to attack the rebellious states of Cilicia, while the larger group pushed south to besiege Sidon and stop the other states in the region from rebelling.

Moreover, Sanda-uarri, king of the cities Kundi and Sissu, a dangerous enemy, who did not fear my lordship and abandoned the gods, trusted in the impregnable mountains. He and Abdi-Milkuti, king of Sidon, agreed to help one another, swore an oath by their gods with one another, and trusted in their own strength.

Inscription of Esarhaddon, RINAP 4:1

|

| Drawing of Assyrian relief of building a palace |

There is a strange prophetic tablet from around this time describing how the Babylonian god Marduk had been angry with his people for their sins and how he had exiled them for seventy years from their lands. The god had however relented and to show his mercy he would turn the tablet upside-down, allowing the prophecy to be fulfilled in eleven years instead of seventy. The cuneiform counting system has 11 and 70 as the same character if they are switched upside down, so this is a way that Esarhaddon was using to allow the gods to be respected and their prophecies fulfilled while still going ahead with his goal to restore Babylon. The themes of the anger of the national god and the seventy years exile of his people is quite an interesting parallel with the writings of Jeremiah around a century later.

In early 678 or late 679, the Assyrians had consolidated the region and contained the Sidonian threat. To stop Egyptian influence in the region they marched south and destroyed a small city called Arza at the very edge of Egypt. Arza’s ruler, Asuhili, was carried off to Nineveh where he was caged and displayed to the populace as part of a menagerie of bears, dogs and pigs. Possibly he was later fed to these animals, as yet another example of Assyrian brutality to anyone who stood against them.

I plundered the city Arza, which is in the district of the Brook of Egypt, and threw Asuḫili, its king, into fetters and brought him to Assyria. I seated him bound, near the citadel gate of Nineveh along with bears, dogs and pigs.

Inscription of Esarhaddon, RINAP 4:1

In 677 Sidon fell and its king Abdi-Milkutti attempted to flee across the sea, but was captured by Assyrian ships. Abdi-Milkutti was decapitated (possibly in 676) and his head sent to Nineveh. Meanwhile the Assyrians demolished large sections of Sidon, took most of its territory and assigned it to Baal I of Tyre who had remained loyal. The city was then renamed after Esarhaddon.

I levelled Sidon, his stronghold, which is situated in the midst of the sea, like a flood, tore out its walls and its dwellings, and threw them into the sea; and I even made the site where it stood disappear. Abdi-Milkutti, its king, in the face of my weapons, fled into the midst of the sea. By the command of the god Asshur, my lord, I caught him like a fish from the midst of the sea and cut off his head.

Inscription of Esarhaddon, RINAP 4:1

|

| Cilician mountains |

In 676 Kundu and Sissu, the small rebel kingdoms in Cilicia, were defeated and their king was also decapitated. The heads of the rebel kings were hung around the necks of the nobles of Cilicia and Sidon and the rebels were paraded in triumph through the streets of Nineveh. Around this time the Assyrians seem to have entered into a full marriage alliance with the Scythians, with Esarhaddon even considering giving one of his daughters to the Scythian ruler. It is possible that the Assyrians were making attacks in the north-east against the Medes around this time, and went as far as the area of present day Tehran. But this seems to have been more of a tribute gathering exercise than anything. The full Assyrian army cannot have been present as there was a similar expedition happening to the south. Again the chronology is rather confused, but it seems as if Esarhaddon was waging a series of rapid small campaigns against his enemies rather than massing his armies for a single large campaign once per year, as was more customary.

To show the people the might of the god Asshur, my lord, I hung the heads around the necks of their nobles and I paraded in the squares of Nineveh with singers and lyres.

Inscription of Esarhaddon, RINAP 4:1

|

| Assyrian gate guardians |

The Assyrian army now marched further south than it had ever marched before, along the southern coast of the Persian Gulf towards a place called Bazu, possibly near present day UAE territory. The march is described as gruelling but after the desert had been crossed the Assyrians engaged in battle with a number of cities and deposed their kings and queens.

As for the land Bazu, a district in a remote place, a forgotten place of dry land, saline ground, a place of thirst, one hundred and twenty leagues of desert, thistles, and gazelle-tooth stones, where snakes and scorpions fill the plain like ants…

Inscription of Esarhaddon, RINAP 4:1

One interesting consequence of this is that one of the kings of Bazu fled away from the Assyrians before coming to Nineveh and submitting to Esarhaddon. This king, Laiale, was pardoned and the province of Bazu was given to him. This small act of mercy was recorded in the Assyrian annals, buried in the ruins of Nineveh and later translated by one of the curators of the British Museum in the 1800’s. The great writer Leo Tolstoy came across the note about Laiale and wrote a short story based on it, called Esarhaddon. It is worth reading in full and can

be found here.

|

| Later artists imagining of Sennacherib's palace |

Laiale, king of the city Iadi, who had fled before my weapons, unprovoked fear fell upon him, and he came to Nineveh, before me, and kissed my feet. I had pity on him and put that province of Bazu under him.

Inscription of Esarhaddon, RINAP 4:1

The dates are a little unclear but during Esarhaddon’s reign the Kedarite Arabs of Adummatu had sent an embassy to Nineveh to beg for the restoration of their gods that had been plundered by Sennacherib in 690. Esarhaddon restored the gods, after having the Assyrian scribes carefully write the praises of Esarhaddon and Asshur upon the idols. Tabua of the Arabs was restored to them as their queen (possibly a ceremonial role as another ruler, Hazael, is referred to as king of the Arabs). When Hazael died, Esarhaddon confirmed Hazael's son Iata as king and supported him against a rebellion. This was not an act of altruism however, as Esarhaddon also increased their tribute during this time.

In 675 the Assyrian armies returned to the troublesome north-western frontier to unsuccessfully besiege the rebellious state of Melid (or Malatya as it is now known). The Elamites under Humban-Haltas II attacked Sippar in southern Mesopotamia, ending the period of peace between Assyria and Elam. Their attack was unsuccessful however and they succeeded mainly in disrupting the religious ceremonies of the sun-god Shamash, whose great shrine was located in Sippar. The Elamite attack was short-lived. Humban-Haltas II was stricken with a mysterious illness that left him suddenly dead; becoming the third Elamite king in succession to die suddenly of an unknown and unexpected illness. There must certainly have been some genetic anomaly in the Elamite royal family at this time.

Humban-Haltas II of Elam was succeeded by his brother Urtak-Inshushinak and the Elamite and Assyrian empires made peace again almost immediately. The Elamites were in no real condition to challenge the Assyrians again and the Assyrians were fighting a number of wars on the northern frontiers against the loose confederations of the Median/Cimmerian/Scythian tribes.

|

| Elamite relief |

The king of Elam entered Sippar and a massacre took place. Shamash did not come out of Ebabbar. The Assyrian marched to Milidu. On the seventh day of the month Ulûlu, Humban-Haltas, king of Elam, without becoming ill, died in his palace. For five years, Humban-Haltas ruled Elam. Urtak, his brother, ascended the throne in Elam.

Babylonian Chronicles: From Nabonassar to Shamash-shuma-ukin

This brings the twenty-five year period to a close. During this time Babylon was destroyed, but it was being rebuilt. The Assyrian empire was now stronger than it had ever been and, once the northern tribal threat had been dealt with, it seems that they were eyeing the rich prizes of Egypt.

There are some questions about the other states however. What was Rusas II of Urartu doing during this time period? Was he behind the tribal attacks on the northern frontiers or was he also being attacked by the horse tribes? What was Gyges of Lydia doing? We can be fairly sure that he was ruling during this time period, but the sources do not tell us much. Was Gyges or Rusas behind the persistent revolts in the Neo-Hittite states? What exactly were the Scythians/Cimmerians/Medes/Persians doing during this time? Were they acting in concert or as scattered tribal entities? What was Taharqa of Egypt planning during this time? Was he the prime mover behind the Sidonian revolt? These questions cannot be answered satisfactorily, but it is worth pondering that many of the motivations of the major players of this time cannot be understood fully. A complete history of this time period would be much more detailed than the account that I have given but the nature of the source materials restricts our gaze.

|

| Drawing of the excavation of Nineveh |

I was able to start the last post with a talking sheep and end it with bowstring eating mice and a poem by Lord Byron. I cannot give such excitement this time but I will end the piece with a later fairy tale that was set in this time period. There was a tale about a sage called Ahikar, who was active in the Assyrian court during the reigns of Sennacherib and Esarhaddon. Being childless he adopted his nephew and taught him many proverbs and wise sayings. But his nephew schemed against his uncle Ahikar and told Sennacherib that Ahikar had plotted rebellion. Ahikar was sentenced to execution, but escaped as he had previously shown mercy to the executioner. Sennacherib later repented of his decision to execute Ahikar and he was restored to the king and sent to the Pharaoh of Egypt to assist him with his wisdom. Ahikar trained eagles to be able to carry humans on their backs to allow humans to fly and to answer the challenge of the Pharaoh to “construct a castle between heaven and earth”. Ahikar answered all the riddles of the Pharaoh with wisdom and returned to Assyria where he was welcomed by the king. His ungrateful and treacherous nephew was delivered to him in chains. Ahikar proceeded to lecture his nephew about moral matters at which point his nephew exploded.

The tale is a strange one but it seems to be quite ancient. The earliest manuscript of it was found in Egypt and is from the Elephantine from the 400’s BC. The tale is clearly Jewish folklore but may have a Mesopotamian counterpart. It is alluded to in the apocryphal book of Tobit and the later folklore of Romania, Armenia and other countries also include the tale. There are clear anachronisms in the text, such as Esarhaddon being the father of Sennacherib rather than vice versa but it is a pleasant little interlude of a tale and I thought that if I couldn’t end a blog post with bowstring-eating-mice, that I should at least end it with children flying upon eagles and building castles between heaven and earth.

|

| Legend of Ahikar |

So the king sprang up and sat with Ahiqar and went to a wide place and sent to bring the eagles and the boys, and Ahiqar tied them and let them off into the air all the length of the ropes and they began to shout as he had taught them, “Bring us clay and stone that we may build a castle for king Pharaoh, for we are idle.” Then he drew them to himself and put them in their places. …

And when Nadan heard that speech from his uncle Ahiqar, he swelled up immediately and

became like a blown-out bladder.

The Legend of Ahikar

Related Blog Posts:

725-701BC in the Near East

Greece from 700-675BC

675-650BC in the Near East