|

| Kylix painted by the Aristophanes Painter |

In the year 419BC a state of uneasy peace had settled over the Greek world. The Sicilian cities were supposedly at peace with each other. In mainland Greece, Athens and Sparta had signed a treaty that had left many Spartan allies unhappy. These allies had begun to form alliances with the hitherto neutral city of Argos, which was unaffected by the war to date and which was a traditional rival of Sparta. Sparta and Athens had had a brief chance to unite against this new power bloc, but the young politician Alcibiades frustrated the Spartan requests and Athens became aligned with Argos, whilst the traditional allies of Sparta, such as Corinth and Thebes, gradually drifted back into their previous alliance with Sparta. This state of affairs meant that the Athenians now had an ally with a land army in the Peloponnese that could in theory threaten Sparta itself for the first time.

In this summer Alcibiades and a contingent of Athenian hoplites went into the Peloponnese (probably by sea) and attempted to influence matters. However the Corinthians and Sicyonians stopped them putting up certain forts. The Argives, encouraged by the presence of the Athenians, went to war with Epidaurus. Epidaurus lay directly to the east of Argos and was the quickest route between Athens and Argos.

|

| Hoplite reenactor in Athens, standing on the Areopagus with the Acropolis in background |

Meanwhile there was a peace conference between the Epidaurians and the Argives, which came to nothing. All the while the Epidaurians were begging their allies to come to their aid, however, due to the sacred month of the Carneia, many of their allies simply didn't send any help at all. After the month of the Carneia, the Spartans marched to the edge of their lands once more, but once more the sacrifices did not allow them to attack.

Instead of attacking however, they slipped a number of troops across the Argolic Gulf that came to Epidaurus and reinforced the garrison there. The Argives were incensed that the Athenians had allowed the Spartans to cross the seas and requested that the Athenians allow raiding expeditions by the freed Messenian helots to be launched from Pylos once more. Pylos was a strategic headland that had been captured by the Athenians in the earlier years of the war. Under the terms of the Treaty of Nicias it was to have been returned to Sparta, but neither the Athenians nor the Spartans had been scrupulous in actually handing back towns or forts that had been taken. The Athenians allowed raiding to begin on Spartan land once more. However, neither the Athenians nor the Spartans were yet technically at war.

|

| Electra, painting by Frederic Leighton AD1869 |

In the year 418, the Argive war against Epidaurus continued, but the city itself was not under siege. The Argives made a surprise attack on the city itself during winter, but the Epidaurians fought them off and the Argives retreated.

Fearing the danger to their reputation if Epidaurus fell, the Spartans summoned their allies from outside the Peloponnese and went to attack the Argives. The Spartans were reinforced with Thebans and Corinthians, while the Argives were reinforced by others from their alliance, but not the hoplite force from Athens. The two sides were on the verge of battle when a prominent Argive named Thrasyllus negotiated a truce with Agis II of Sparta. The two armies broke away from battle and were both extremely angry with their leaders for making peace instead of war. A four month truce was agreed to by the parties.

Thrasyllus' property was confiscated and he was lucky to escape with his life. In Sparta, the ephors were so furious that they threatened Agis with an enormous fine and were going to tear his house down. Agis II promised instead to win a great victory for Sparta in recompense, but the Spartans were angry enough that they gave him ten counsellors who would oversee the decisions of the king.

Meanwhile an Athenian contingent of hoplites led by Alcibiades arrived in Argos only to hear that the war had already ended. Alcibiades argued that the Argives had no right to make peace or war without their allies and that the treaty between the Argives and Spartans was therefore void. The Argives willingly abrogated the treaty and the Athenians and Argives, with their Mantinean allies moved against the Spartan city of Tegea.

Tegea controlled the northern entrances to Laconia and the loss of Tegea would effectively block the Spartans into their own narrow territory. This was probably the intention of attacking Tegea rather than Lepreum, as had been suggested by the Eleans.

The Spartans acted swiftly and bypassed the Argives at Tegea, moving northwards to attack Mantinea, which they judged would draw the alliance away from Tegea. The Theban and Corinthian allies were no longer with the Spartans, but the Spartans had mustered their full army and had perhaps around 9,000 hoplites in the field, including their elite Sciritae light infantry, which had the honour of holding the left flank.

|

| Ruins at city of Mantineia |

The next day, the Spartans and the Argives gave battle in what was to become known as the First Battle of Mantineia. The Argive right wing was composed of the Mantineans (who were fighting for their homeland), the Arcadians, and the finest fighters of the Argives (an elite force known as The Thousand). The Argives mostly composed the centre of the force and the Athenians held the left wing.

The Spartan left wing was composed of the Sciritae, hardy light troops who were trusted to fight like full Spartiates. The Spartans made the main body of the centre, with the Tegeans holding the right wing of the Spartan army, bolstered with some Spartiates to strengthen them. Thus Agis had placed his main strength in the centre.

|

| Illustration of a Spartan warrior bearing a shield with a lambda device |

Both left flanks seem to have immediately come into danger. The Argives broke the Sciritae and the Spartan forces and their elite troops were threatening the Spartan king. However on the other side of the battle, the Tegeans and the troops on the Spartan right had routed the Athenians. The Spartan right then wheeled in on the elite Argive force in the centre, where the fighting was hottest and threatened to surround them. However the Argives had fought well indeed and the Spartans eventually allowed them to escape, whether through policy or exhaustion.

Agis also on perceiving the distress of his left opposed to the Mantineans and the thousand Argives, ordered all the army to advance to the support of the defeated wing; and while this took place, as the enemy moved past and slanted away from them, the Athenians escaped at their leisure, and with them the beaten Argive division.

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 5 written circa 400BC

It was a great Spartan victory and one that had enabled them to brush off the shame of their men surrendering at Pylos. They had once more proven themselves the strongest fighting force in Greece. The Argives had fought well, but their courage was no match for Spartan discipline, tactics and numbers. The Athenians had not fought particularly well and suffered reputational damage, as well as suffering the death of Laches, who was one of their better generals. The Argives had lost perhaps 700 men, while the Athenians had lost about 200. Spartan losses were perhaps around 300, although casualty figures are notoriously unreliable for ancient battles.

|

| Lambda symbol on a modern reproduction of a hoplite shield |

Meanwhile the Epidaurians attacked Argos upon hearing of the Argive defeat. The Eleans had not been present at the battle, as they had marched away to carry on their own war against Lepreum and they marched to the aid of Argos with a substantial force of perhaps 3,000 hoplites. Athenian reinforcements arrived as well to aid the beleaguered Argives. These reinforcements pushed the Epidaurians back and the city of Epidaurus was put under siege.

The Argives had had enough of war however, and their elite fighting force, the Thousand, wanted to install an oligarchy instead of the traditional Argive democracy. The Argives thus made a peace with the Spartans that was to last for 50 years. The previous leagues and alliances were repudiated. The Athenians thus had to evacuate the forts near Epidaurus.

|

| Ruins in ancient Sparta |

In the year 417 it proved that the oligarchy at Argos was to be short-lived and the Argives overthrew the oligarchs, who were then slain and exiled. The Spartans did not actually provide much help to their allies in Argos, but war now threatened once more between Argos and Sparta, save that this time Argos was nearly without allies. They tried to build Long Walls to the sea, to once again allow an Athenian alliance, but the Spartans broke down the walls before they were built. There was once more an alliance of sorts between Athens and Argos, but with Argos being much weakened.

Alcibiades was to blame for much of this. He had been the prime mover in the Argive alliance and in the breaking of the truce between Thrasyllus and Agis. He may have been the leader of the Athenian contingent that did so badly in the Battle of Mantineia and bears much responsibility for the deaths that occurred there.

|

| Greek helmets |

In this year it is said that The Clouds, a comedy by Aristophanes making fun of Socrates, was restaged. This version of the play was slightly rewritten from its earlier form and it is this slightly later version that we have handed down to us today.

In the year 416 the Athenians, who were labouring in a strange limbo between peace and war, sent some more troops to Argos, once again under the command of Alcibiades, and assisted the commoners of Argos in hunting down pro-Spartan oligarchs within their ranks. This must have been a dismal assignment, as civil war always is.

The Athenians also attacked the island of Melos. Melos was a Spartan colony in a small island to the southeast of the Peloponnese. It was not part of the Athenian Empire and had previously been attacked by the Athenians. They were a relatively small and helpless state, with no real navy or army that could hurt or harm the Athenians. The only real reason to attack Melos was because it was an island and the Athenians believed that all islands in the Aegean should be subject to them.

|

| Replica plaster bust of Thucydides |

Since you know as well as we do that right, as the world goes, is only in question between equals in power, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.

Athenians speaking to the Melians in the Melian Dialogue. Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 5 written circa 400BC

The Athenians besieged the city on the island of Melos. Meanwhile, the Spartans, who as yet did not go to war against Athens, decreed that anyone could attack the Athenians if they wished. The freed Messenian helots continued to raid Spartan lands from Pylos. Corinth went to war against Athens. The Argives fought against their exiles who were in the nearby city of Phlius. But still Greece was technically at peace.

Meanwhile in Sicily the peace had broken down once more. Segesta, a city in the far west of the island, was at war with Selinus, also in the west of Sicily. The Selinuntines were Dorians, while the Segestans were not. The Dorians were particularly strong in Sicily, with Syracuse and Acragas both being Dorian cities. The Segestans appealed to the Athenians in an attempt to counterbalance the power of the Selinuntines' potential allies. The city of Leontini was also engaged in a struggle with Syracuse and appealed to Athens.

|

| Coin of Athens |

In Athens itself around this time, although the dates are somewhat unclear, the populace was split into numerous parties. There was the party of Nicias, who was a respected general and a friend of Sparta. This would have included some aristocrats, but generally this might be referred to as the peace party. They might have viewed themselves as natural successors to the aristocratic democracy of Cimon some decades earlier.

Then there was the party of Alcibiades, which also included a number of aristocrats, particularly young aristocrats, who hoped to win glory and wealth in the wars. They might be referred to as the war party and certainly favoured war, particularly favouring the Argive alliance. They would also have laid claim to the legacy of Pericles, to whom Alcibiades was related. However, after the defeat at Mantineia, they may have been discredited.

|

| Ostracon bearing the name of Hyperbolus |

Hyperbolus proposed an ostracism either in this year, or the years immediately before or after. There was a waiting period after the proposal of an ostracism. During this time Nicias and Alcibiades made a secret agreement that their followers would band together and ostracise Hyperbolus, who was widely viewed as being a buffoon and too low a target for this tactic. Ostracism had usually been used against nobles and it was viewed as a punishment reserved for the great and the good.

Hyperbolus was duly ostracised and Nicias and Alcibiades were safe. The Athenians thought the whole thing immensely funny, but eventually felt that they had dishonoured one of their institutions. A comic poet wrote that "The man deserved the punishment, but the punishment did not deserve the man". Thus the ostracism of Hyperbolus became the last ostracism in Athens. It would have served them better to have ostracised either Nicias or Alcibiades; both of whom were extremely dangerous to Athens in their own unique ways.

|

| Later statue of Euripides |

The play is a complex exploration of faith and hope and the ways of gods and men. While many Athenians must have found it interesting, we know that they did not grant it the prize, but instead gave the prize to a dramatist named Agathon.

Plato's Symposium uses this as festival as its dramatic setting. Plato describes a banquet held at the house of Agathon. At the drinking party, the guests all compose a speech about the nature of Love. There are a number of guests, including the comic poet Aristophanes and the philosopher Socrates, who are both presented as being on good terms with each other. There is a doctor known as Eryximachus said to have been at the party, who was the son of another doctor known as Acumenus. These were real people who were well-known in Athens at the time. After all the guests speak of love, the party is gate-crashed by Alcibiades, who is drunk. He speaks drunkenly in praise of Socrates and then all the party get drunk. Finally Socrates, who is not drunk, leaves quietly when everyone has fallen asleep.

It is a short, but memorable work by Plato, and it is very likely that Agathon did celebrate after winning his prize. It is even possible that some of those mentioned by Plato attended his party. But we must remember that the Symposium is a philosophical fiction by Plato rather than anything resembling a history.

|

| Alcibiades entering the Symposium. Painting by Feuerbach AD1869 |

Plato, Symposium, written circa 385BC

Agathon was a prominent and interesting playwright in his own right, despite being best remembered from the Symposium. He was friendly with Aristophanes, who nevertheless fiercely criticises him in later works. He didn't exclusively use mythological subjects in his plays, instead creating new plots and stories, something which many Athenians found offensive. He later moved to the court of the king of Macedon where he died. In an unusual aside, Agathon was one of the few people in Classical Greece who could be described as homosexual in the modern sense. The classical world had many same-sex relationships, but these were generally transient and with wide age-disparities. Agathon had a long-term relationship with a man of a similar age. It was unusual enough for it to be mentioned in the Symposium and is worth remembering here.

|

| Propylaea gateway to the Acropolis in Athens viewed from the Areopagus Hill |

Around this time it is suitable to mention Antiphon of Rhamnus. He was a logographer, a type of professional writer that we would generally refer to as a speechwriter. He was active in the affairs of the state, where he favoured a generally oligarchic/aristocratic form of government. He wrote speeches for people to deliver, but generally he did not address the people himself. A number of his speeches survive, including a vivid denunciation of somebody's stepmother in a case of poisoning. The majority of his surviving speeches are speech templates however rather than speeches in and of their own right. Apparently the worthy Antiphon kept a stock set of replies for various arguments, so that someone prosecuting for murder or accidental homicide should never be at a loss for words. Antiphon of Rhamnus is known as the first of the Ten Attic Orators, famed in antiquity, whose speeches were preserved for students of rhetoric.

It seems that there are a number of sophistic treatises dating from this time that are ascribed to "Antiphon". Even from classical times, scholars have been unsure if this Antiphon was the same person as Antiphon of Rhamnus or should be classed as a separate individual, usually referred to as Antiphon the Sophist. Scholars are still unsure on this. If the two individuals are one and the same Antiphon this would suggest that Antiphon of Rhamnus was an accomplished man of letters indeed. But as yet he would make no speeches himself, preferring to avoid courts.

|

| Later herm bearing the head of Alcibiades |

In the Assembly, Nicias argued against the expedition, but was overruled and the expedition was put under the command of Alcibiades, Nicias and Lamachus. Alcibiades was seen as being a good general, but hot-headed and the Athenians felt that Nicias would be a good counter to Alcibiades, with Lamachus adding even more military expertise. Five days afterwards, Nicias, accepting that the expedition would be under his command, made an appeal to the Assembly, saying that the power of Sicily was great and that only a truly gigantic fleet would be able to conquer it. He probably hoped to dissuade the Athenians from undertaking the expedition, but all that happened was that the Athenians became even more enthusiastic and voted for an expedition of 100 triremes, numerous transport ships, 5,000 hoplites and numerous other mercenaries. All told it was a vast expedition, but not necessarily the largest that Athens had ever sent. It is likely that the Egyptian expedition in previous decades was at least this large.

All of Athens now became abuzz with preparations for the new war and the rumour of the expedition spread throughout the Greek world. An expedition of this size could not be hidden, but the Syracusans were slow in realising the danger of what was coming against them. Syracuse was not technically the target of the expedition, but any force of this size coming to Sicily must have been expected to inevitably clash with the greatest city on the island. Still, the Syracusans could not believe that, with the nearby Spartans so hostile, that the Athenians would dare risk such an attack on a nation so far away.

|

| Coin of Athens |

This calls for some explanation. Greek houses of the time often had statues at boundary markers. These were generally of the form of squared pillars topped with a bust of a head, quite often a male head of the god Hermes, but very often of other divine or human figures. The figures generally had male genitalia about halfway down the square column. These ubiquitous figures were known as "herms". What had happened was that the faces of these were smashed and hacked, with the exception of a herm near the house of the orator Andocides, who immediately fell under suspicion.

The incident was seen as very serious. Such a desecration suggested an evil omen for the coming expedition. Others felt that this type of concerted attack suggested the activity of enemy agents, perhaps Spartans or Syracusans, or their sympathisers, active within the city. Suspicion fell on Andocides, whose herm had not been touched, and he was imprisoned. Perhaps to save himself, he began to accuse others of involvement. The common people feared the aristocratic youths, who were filled with the foreign learning of the sophists and philosophers and who laughed at the gods and the old ways. Many of the aristocrats also had ties to, or admiration, for the arch-enemy: Sparta.

|

| Curse inscription and magic amulet from Athens, dating from this period |

This threw Athens into an uproar. This was an offence punishable by death, but Alcibiades was at this point nearly the leading man in the state. His extravagant and unusual behaviour made the charge seem plausible enough however. His enemies were delighted and his supporters were outraged. Alcibiades protested his innocence vigorously and demanded a trial before the fleet set sail against Sicily. However, this request was not granted, as his opponents said that his trial could wait until his return from Sicily. This was so that when additional accusations were levelled, a new trial could be ordered and Alcibiades recalled, so that the soldiers, with whom he was popular, could not sway the jury.

Reluctantly and with a cloud of uncertainty over his fate, Alcibiades set sail with the Athenian navy towards Sicily. The expedition had other problems as well. The first was that the expedition was a large one, but had no clear goals. Were they to merely aid Segesta against Selinus, or to try and conquer all of Sicily? Most importantly, did their obligations to help the city of Leontini automatically commit them to attack the Syracuse, which was the enemy of Leontini? When the fleet reached Rhegium at the toe of Italy it became clear that the city of Segesta did not have the wealth that it had promised and was going to be unable to finance the expedition.

|

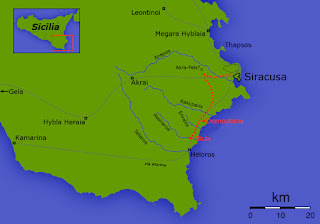

| Map showing the |

Nicias' strategy was not great and ancient authors have criticised him for it. But in reality Alcibiades strategy was not great either. Few would be interested in allying with such a force, which was too large to be easily quartered, yet not large enough to be guaranteed of conquering Syracuse, which was a city-state comparable to any polis save Athens and Sparta. Lamachus' strategy was the best one, as it involved hitting their greatest foe while the terror of the fleet was at its height and before the Syracusans could prepare. But it would also involve the diplomatic odium of being a surprise attack without a declaration of war. In the end Alcibiades' strategy was adopted, to little avail.

|

| Modern statue of Thucydides |

Knowing now that the expedition was aimed at least partly at subduing Syracuse, the Syracusans were mustering an army and a navy to resist the Athenians. They were led in this by Hermocrates, who seems to have been the leader of the oligarchic party in Syracuse. The Athenians made a show of force against Syracuse, but the city was not overawed.

Meanwhile back in Athens, the people were almost in a state of hysteria. Accusations and counter-accusations of treason, blasphemy and espionage were made. New accusations against Alcibiades were made and thus the Salaminia, one of the two state triremes that was constantly at sea in the service of the Athenian state, was sent to Sicily to recall Alcibiades to face trial. The opponents of Alcibiades believed that he was aiming at nothing less than a complete overthrow of the democracy and the establishment of himself as tyrant. This is not outside the bounds of possibility.

To return to Alcibiades: public feeling was very hostile to him, being worked on by the same enemies who had attacked him before he went out; and now that the Athenians fancied that they had got at the truth of the matter of the Hermae, they believed more firmly than ever that the affair of the mysteries also, in which he was implicated, had been contrived by him in the same intention and was connected with the plot against the democracy.

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 6, written circa 400BC

When the summons for Alcibiades to return to face trial reached the expedition, Alcibiades took the news quite calmly and set sail as a free man in his own ship to return with the Salaminia to face trial. However, when the ships put into the port of Thurii, Alcibiades disappeared and could not be found. The Salaminia sailed onwards and the Athenians, now convinced of the guilt of the coward Alcibiades who would not face trial, passed a sentence of death in absentia on him. Alcibiades meanwhile sailed secretly to the Peloponnese and now offered his services to the Spartan state.

|

| Maps showing the cultures of Sicily at the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War |

The Syracusans themselves had become so emboldened by the lack of Athenian movement that they led an army against the Athenians, marching northwards towards the Athenian base at Catana. They were particularly proud of the fact that they had excellent cavalry, by Greek standards, and the Athenians had very few cavalry with their expedition. The Athenians had sailed towards Syracuse and the Syracusans followed them back towards their city. A battle ensued, known as the First Battle of Syracuse where the Athenians soundly beat the Syracusans. However, the Syracusan cavalry proved their worth and despite the Athenians thoroughly routing the Syracusan infantry, the unbeaten cavalry kept them from inflicting great casualties in the pursuit.

|

| Athenian grave stela |

The large city of Camarina was appealed to by both Athenians and Syracusans, but they remained officially neutral, while secretly providing some small aid to the Syracusans. Whatever dreams the Athenians may have had of effortlessly "liberating" Sicily were not to be. The Athenians, realising that they needed more resources, sent messages to Athens asking for more money to pay the soldiers and sailors and perhaps to bribe certain politicians in Sicily.

The Syracusans meanwhile reorganised their army, restricting the number of their generals, actively strengthening their defences and allowing Hermocrates to oversee the overall defence of the state. They also sent envoys to Corinth and to Sparta, imploring them for aid and also begging them to attack Athens in mainland Greece. The Corinthians and the Spartans agreed to send some small reinforcements to Syracuse; military advisors so to speak, but despite information from Alcibiades on Athenian weaknesses, the Spartans refrained from direct attacks on Attica as yet.

|

| Woodland near site of Decelea |

In this year Xenocles won the prize for tragedy in the Great Dionysia in Athens. Little is known of Xenocles, save that the comic playwright Aristophanes hated him. According to Aristophanes, "Xenocles, who is ugly, makes ugly poetry." Nevertheless in this year his trilogy of plays won the prize. I doubt Xenocles would be pleased at learning that he is remembered by posterity merely for winning once and for being disliked by Aristophanes, but at least his name is remembered for that much at least. He had a grandson who would later become a tragic playwright as well, of whom even less is known.

Euripides put forward the Trojan Women as one of the plays of his trilogy that year. This was a play along similar themes as his earlier play Hecuba. It dealt with the fate of the conquered after the fall of Troy. Hecuba, Cassandra and Andromache are horrified by the fates that await them, as slaves of the various Greek generals, amid the horror of the loss of their husbands and fathers. Andromache learns that her infant son Astyanax is to be murdered by the Greeks, hurled to his death from the battlements of Troy, for fear that he should avenge his father. It is a dark play, perhaps inspired by the massacre and mass enslavement of the Melians in the previous year. The anti-war themes of the play have seen it performed and adapted many times throughout history.

|

| Pnyx Hill in Athens, the site where the Athenian Assembly met and voted |

Around this time Diagoras of Melos was said to have been banished, or to have fled, from Athens. It is possible that he feared being prosecuted for impiety and later classical writings refer to his as an atheist. It is said that he chopped up a wooden statue of the god Heracles to roast some lentils. It is said that he also spoke openly of the secrets of the Eleusinian Mysteries. He is the most famous atheist of that time, but I wonder if this is a later misreading of the events at the time.

Diagoras was from Melos, the island that had in the previous year been subject to a mass enslavement and genocide by the Athenians. It is no surprise that he should have become extremely hostile to the Athenian state and also to have been subject to great mistrust from the Athenians. The Athenians were also in a state of near hysteria regarding the desecration of the herms and the profanation of the Mysteries. In this atmosphere Diagoras would have been a definite target, even if he had no hostile opinions against the gods. He would doubtless have looked to flee and his flight would have been taken by his enemies as proof of all manner of impiety.

|

| Vase painted by the Amykos Painter |

Also, around this time various vase painters flourished. The Amykos Painter, Chrysis Painter, Eretria Painter, Reed Painter and Aristophanes the vase painter all were active around this time period. As pottery is so durable, many of their works have survived and can be seen today in museums around the world. The Reed Painter specialised in painting white-ground works, while the other painters mentioned were red-figure painters. All were from Attica, which even in this time of war, still produced some of the finest high-status ceramics in the Greek world.

In the year 414 the Spartans moved to attack the Argives, but turned back because of an earthquake. The Argives then attacked the Spartans and took much plunder from the borderlands. There was civil war in Thespiae in Boeotia, where the common people tried to overthrow the oligarchy, however the Thebans came to the aid of the oligarchs and the leaders of the uprising fled or were executed. The Spartans had also dispatched the general Gylippus to aid the Syracusans in their war effort.

In Sicily, the Athenians had belatedly realised the crucial importance of attacking Syracuse and sailed against it once their reinforcements of cavalry, archers and money had arrived from Athens. Landing swiftly and defeating a Syracusan sally, the Athenians began to swiftly build a wall around the city that would wall in the Syracusans. When the city was invested by land the Athenian navy would keep the Syracusan ships bottled up and the city, which was not prepared for a siege, would fall.

|

| Maps of the walls and counterwalls of the Athenians (blue) and the Syracusans (red) |

Argive and Spartan armies clashed once more in mainland Greece and the Argives were defeated. However this time the Athenians came and attacked the Spartans with the crews and marines of thirty ships. The Spartans, who had up until this point considered the treaty between Athens and Sparta to still be in force, even if stretched to its utmost, now considered that the treaty was utterly null and void. However, they did not immediately go to war with the Athenians, as the campaigning season had passed.

In Sicily, the extension of the wall towards the sea to the south had caused great panic in Syracuse and there was talk of negotiating a surrender. However, at this point the Spartan, Corinthian and other allied reinforcements arrived under the command of a capable Spartan general named Gylippus. Gylippus carried on the resistance much as before, but in a more determined manner and in building a much longer counter-wall up the heights of the Epipolae.

Nicias was beginning to despair of the entire enterprise, which he had argued against from the start, then been placed unwillingly in charge of, then unwillingly prosecuted. He wrote a letter to the Athenians complaining of the great difficulties of the siege and the dangers caused by the reinforcements from Corinth and Sparta. The Athenians heard the letter and sent a fleet to stop any more reinforcements from reaching Sicily from Corinth. Meanwhile, the Spartans were preparing to resume the war fully once more and to carry operations into Attica again, however, the campaigning season was over so their preparations would be put into effect the following year.

|

| Later herm bearing the name and portrait of Aristophanes |

The other plays do not survive, but The Birds by Aristophanes is still extant. It is a light-hearted affair where certain Athenians decide to ally with the birds and overthrow the Olympian gods in the sky. The comedy centres mostly on this outlandish idea and it is generally just a nice piece of escapist comedy that has no real bearing on current events, although a number of well-known Athenian characters are mentioned and occasionally lampooned.

Around this time the play Ion is written by Euripides. It is not his most famous play, but it is said to be among his more innovative ones, featuring the legendary king of Athens named Ion, who gives his name to the Ionian tribe of Greeks.

In the year 413 the Spartans launched another invasion of Attica in full force. While here, they not only ravaged the countryside as they had done in the previous phase of the war, but they also, on the advice of the traitor Alcibiades, built a fortification at Decelea, near the Parnitha Mountains. This fortress was far enough away from Athens that the Boeotians could support it if the Athenians ever attacked in strength. It also enabled the Spartans to raid Attica year round, and gave a place for the slaves of Attica to flee to. It particularly disrupted the workings of the silver mines in Laurion, which relied entirely on a large slave-labour force, working under gruelling conditions. These slaves now had a guaranteed haven to flee to. Thucydides records that 20,000 slaves defected to the fort at Decelea, although this was probably over the course of a few years of war.

|

| Athenian grave stela |

Gylippus decided to use the ships of the Corinthian reinforcements to attack the Athenians on sea. This attack was unsuccessful, but the Syracusans were successful in a land attack on the Plemmyrium, which was the hilly area on the southern end of the mouth of the harbour. This meant that the Athenian control of the harbour was threatened and that supplies could not be safely landed on that shore.

Meanwhile the Athenians, despite their troubles in Attica, had sent a huge relief force towards Sicily under the command of Eurymedon and Demosthenes. This was almost as large as the first force, but had fewer triremes with it. As the war between Sparta and Athens had now resumed in full force these two generals took their time on their journey, levying troops where they could, strengthening the fleet at the vital garrison port of Naupactus and ravaging Spartan territory on their way. News of their approach reached the Syracusans and Gylippus who decided to attack the Athenian expedition under Nicias before it could be reinforced.

|

| Coin of Syracuse |

The Syracusans could not long relish their triumph, as soon Demosthenes and Eurymedon arrived with their great armament of triremes, hoplites, archers and supplies. They must have been horrified to see the decline of the initial expedition force and in what straits the army and fleet under Nicias had sunk to. Demosthenes urged an immediate attack, while his men were fresh. He had brought an additional 5,000 hoplites, bringing their combined strength to perhaps 8-9,000 hoplites (as some had undoubtedly died in the previous engagements). This was not a huge force, but it was supported by a large number of lighter troops and the rowers of the triremes who could also be armed. Nicias, Demosthenes and Eurymedon would have had at least 20,000 fighting men at their disposal at this point and this was a formidable force indeed.

|

| Vase painted by the Eretria Painter |

However, like all good plans, it can be ruined by simple bad luck and unforeseen factors. The night attack, which was always risky in ancient warfare, was complicated by the fact that both sides, when they would attack, would sing the paean, a type of battle song meant to inspire courage in their own men and fear in the enemies. However, due to there being Dorians and Ionians on the Athenian side and only Dorians on the Syracusan side, the paeans of the Argives (Athenian allies who were of the Dorian tribe) made it sound as if the Syracusans were fighting in and behind the Athenians. This eventually panicked enough of the Athenian force that they fled and many were cut down or fell to their deaths from the heights. As with all night battles at least some of their own side fought each other.

But what hurt them as much, or indeed more than anything else, was the singing of the paean, from the perplexity which it caused by being nearly the same on either side; the Argives and Corcyraeans and any other Dorian peoples in the army, struck terror into the Athenians whenever they raised their paean, no less than did the enemy. Thus, after being once thrown into disorder, they ended by coming into collision with each other in many parts of the field, friends with friends, and citizens with citizens, and not only terrified one another, but even came to blows and could only be parted with difficulty. In the pursuit many perished by throwing themselves down the cliffs, the way down from Epipolae being narrow…

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 7, written circa 400BC

|

| Athenian grave lekythos |

The Syracusans were now bolstered by more reinforcements from the Peloponnese and confident that they were a match for the land army. At this point even Nicias agreed that they must retreat, and the Athenian expedition prepared to embark. However on the 28th of August there was a lunar eclipse. This was interpreted by Nicias to mean that they must wait 27 days. Later classical writers say that this was a mistake and that he should have only waited 3 days, but 27 makes more astronomical sense. I imagine that the astrologers changed their mind about the appropriate time of the omen after seeing the consequences of Nicias' decision.

However, they now decided to attack the Athenian navy at sea. A great battle took place in the harbour and once more, the strengthened prows of the Syracusan ships defeated the Athenians in an ugly, but effective, head-to-head contest. The Athenian general Eurymedon was killed in this battle, leaving only Demosthenes and Nicias in command of the expedition.

|

| Reconstruction of a trireme |

This meant in effect an Athenian defeat. If they could not force the mouth of the harbour, then they could not escape. After losing half their ships and retreating, the Athenians disembarked. Demosthenes urged the men to return to the ships and fight once more, and Nicias agreed, but the men refused. They may have believed that even if they fought through, that they had lost too many ships to carry the men homewards. They had also lost all hope of victory.

The sea-fight having been a severe one, and many ships and lives having been lost on both sides, the victorious Syracusans and their allies now picked up their wrecks and dead, and sailed off to the city and set up a trophy. The Athenians, overwhelmed by their misfortune, never even thought of asking leave to take up their dead or wrecks, but wished to retreat that very night. Demosthenes, however, went to Nicias and gave it as his opinion that they should man the ships they had left and make another effort to force their passage out next morning; saying that they had still left more ships fit for service than the enemy, the Athenians having about sixty remaining as against less than fifty of their opponents. Nicias was quite of his mind; but when they wished to man the vessels, the sailors refused to go on board, being so utterly overcome by their defeat as no longer to believe in the possibility of success.

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 7, written circa 400BC

|

| Coin of Syracuse |

The Syracusans, who still feared the Athenian host, were wary lest the Athenians should march overland and reach another Sicilian city. There were enough troops left to be formidable if they could find a base. The Syracusans spread a rumour that there were armies guarding the roads inland and this delayed the Athenian retreat.

On September 13th the Athenians finally began their slow and painful retreat. They abandoned their wounded and unburied dead and crossed the Anapus River, hoping to reach allies in the interior, possibly as far west as Catana. Demosthenes and Nicias encouraged their men as much as they could and split the army up into two divisions; each general commanding a division.

|

| Vase painted by the Eretria Painter |

This decision was of no avail. The Syracusans caught up with the Athenian force later that day. The division of Demosthenes had fallen behind and was surrounded, taking shelter in an enclosure of sorts where they were besieged by the Syracusans. Eventually Gylippus offered Demosthenes a surrender option, which would see the prisoners enslaved, but not killed. 6,000 soldiers surrendered here.

While the rear-guard under Demosthenes had been destroyed by the Syracusans, Nicias had been leading his army on at speed, forcing the crossing of the Erineus River, but hearing of the disaster that had befallen the troops under Demosthenes' command. Nicias tried to negotiate with Gylippus, but Gylippus refused the terms offered. Nicias pressed onwards.

|

| Map showing the route of the Athenian retreat |

It was here that the main Syracusan army came upon the remnants of the expedition and in the confusion and disorder the battle turned into a massacre, with the Syracusans and the Peloponnesians slaughtering the Athenians in droves. Nicias surrendered himself to Gylippus and asked him to stop the killing, which was eventually done, but not before the vast majority of those with Nicias had fallen. Some few fugitives escaped, but aside the 1,000 taken as slaves, few Athenians survived from this place.

The Athenians pushed on for the Assinarus, impelled by the attacks made upon them from every side by a numerous cavalry and the swarm of other arms, fancying that they should breathe more freely if once across the river, and driven on also by their exhaustion and craving for water. Once there they rushed in, and all order was at an end, each man wanting to cross first, and the attacks of the enemy making it difficult to cross at all; forced to huddle together, they fell against and trod down one another, some dying immediately upon the javelins, others getting entangled together and stumbling over the articles of baggage, without being able to rise again. Meanwhile the opposite bank, which was steep, was lined by the Syracusans, who showered missiles down upon the Athenians, most of them drinking greedily and heaped together in disorder in the hollow bed of the river. The Peloponnesians also came down and butchered them, especially those in the water, which was thus immediately spoiled, but which they went on drinking just the same, mud and all, bloody as it was, most even fighting to have it.

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 7, written circa 400BC

Nicias and Demosthenes were executed by the Syracusans, probably against the wishes of Gylippus. Demosthenes was not liked by the Corinthians, Syracusans or Spartans. Nicias knew too much about possible traitors in the city of Syracuse. Now that victory was won, it was better for the continued peace of the city for that knowledge to go to the grave, and so they killed him.

|

| Quarries in Syracuse said to be the same quarries the Athenians were held prisoner in |

There was some small measure of comfort for some few Athenians from an unlikely source. It appeared that some Syracusans were passionate about the poetry and plays of Euripides, and any Athenian who could quote Euripides was sometimes given food and drink for it and in certain rare cases, even given their freedom. Those who did return eventually to Athens often visited the playwright to thank him.

The Sicilian Expedition was the most catastrophic defeat that Athens had yet suffered in any of its wars. The total loss of men was at the very least 20,000 and possibly as high as 50,000. Many of these of course were not Athenians, but from the armies of their allies, but it was still an extraordinary loss for the Athenian Empire. They had also lost 200 ships and effectively lost control of the seas. In addition to this they had gained a powerful new enemy, as Syracuse now wanted revenge upon Athens and was preparing to send a fleet to mainland Greece to aid the Spartans.

|

| Lekythos painted by the Reed Painter |

The Athenians were shocked and stunned at the news of their defeat, but once they had poured out their anger and grief at their loss they began embark on an immediate program of ship building. They had also maintained a fleet of 100 triremes to be used as reserves in case of any disaster. These were now deployed, and these, combined with the existing fleets in the Aegean, Black Sea and at the naval base at Naupactus, still meant that Athens had probably the largest fleet in the Greek world. It was no longer unassailably large however. The men would prove more difficult to replace and the skilled crews could not be replaced at all. Athenian ships would now be roughly equal in ability to the ships of other cities.

Meanwhile Agis II, who was at the Spartan fortress of Decelea, received word that the Athenian tributary states were planning to revolt. Euboea, Lesbos and Chios were all preparing to revolt and the Spartans promised to aid them.

The Persian satrap of Lydia, named Tissaphernes, from one of the most prominent Persian families, sent a message to Sparta to let them know that he wished to join the war against Athens, as did the Persian satrap of Phrygia, Pharnabazus. All of these new allies in the war against Athens made the imminent defeat of the Athenians seem a certainty to all observers in the Greek world.

Tissaphernes had been sent by the king Darius II to crush the rebellion of a rebel satrap of Lydia, named Pissuthnes. This had been done, however Pissuthnes' son Amorges still continued in rebellion and it seems that the Athenians had been providing some form of assistance to him. Thus, even if the Sicilian Expedition had not failed, it is not unlikely that the Persians would soon have been at war with the Athenians.

Around this time a rift appeared between the Athenian exile Alcibiades and the Spartan king Agis II. Rumours began to spread that Alcibiades had slept with Agis' wife Timea and that his son Leotychidas was in fact the son of Alcibiades.

|

| Coin of Archelaus I of Macedon |

Another thing worthy of mention in this year is that Diocles of Syracuse, a prominent citizen of Syracuse, who had been noteworthy in pressing for the harshest penalties for the Athenians, was put in charge of reorganising the laws of the city. He imposed terms limits for certain magistrates, nominated a group of citizens, including himself, to create a new law code, and finally forbade the wearing of arms in the agora of the city under pain of death.

In this year it is said that the comic playwright Hegemon of Thasos put on a play known as the Gigantomachia, which was said to be so funny that even though the news of the defeat of the Sicilian Expedition reached the theatre, that the audience stayed in their seats and continued watching until the end. This is a later story and probably at least partly untrue.

|

| Theatre of Dionysus in Athens |

In the year 412 the entire focus of the war shifted eastwards. The Syracusans had sent a fleet of 35 ships under the command of Hermocrates to aid the Spartans, but the Persian satraps were offering to pay for the upkeep of a Spartan navy. In return they wanted a free hand to collect tribute from the Ionian cities on the coast of Asia Minor; cities that had been under Persian rule before the wars earlier in the century. These cities included some of the wealthiest cities of the Athenian Empire. The straits of the Hellespont and Bosphorus were also vital to the Athenians, as their grain came to them from the region of the Black Sea. Thus, if the Spartans wanted to support their new fleets and the Athenians wished to preserve their empire, both sides must struggle for control of Ionia and the Hellespont.

The Spartans readied a navy and sent Alcibiades with it to raise Chios in open revolt. The Athenians caught and blockaded some of this fleet, but Chios rose in rebellion once Alcibiades reached it, as did some other important allies of Athens, including the Milesians. Shortly afterwards the cities of Lesbos were persuaded to revolt. However the Athenians brought Clazomenae and Lesbos back under control swiftly and the initial revolt did not spread.

The Spartans and the Persians under Tissaphernes now made a treaty saying that the King of Persia would finance the Spartan war effort and use his own troops as well in the war, but that the lands that had once been ruled by the Persians would be ruled by them once more. This clause may have been kept secret from the Ionians, who disliked the Athenians for their heavy taxation, but had no great desire to swap Athenian taxation for Persian taxation.

Around this time there was a civil war in Samos, whereby the common people overthrew the aristocrats. This tied them much more closely to Athens, which generally favoured democracies, while Sparta favoured oligarchies.

The blockaded Peloponnesian fleet broke out and made it across the Aegean, where it joined the other Peloponnesian and Chian ships. Many small naval actions were fought between the Athenians and their enemies, but there were no great decisive battles. The Athenian navy reorganised and won an indecisive victory against the Peloponnesians, Chians and Milesians near Miletus, but the news of an approaching Peloponnesian fleet prevented the Athenians from following up any of their partial successes. The Athenians then began to besiege Chios.

Tissaphernes then ordered the army and navy to move against Teichiussa. Here they were able to swiftly capture the city and take Tissaphernes' enemy Amorges prisoner.

At some point in this year, Alcibiades seems to have appointed himself as a personal representative of the Spartans with the Persian satrap Tissaphernes. He began to advise Tissaphernes to not give the Spartans everything they asked for. He particularly advised him not to bring up the Phoenician fleet, which would be able to end the war decisively one way or the other. Because of the bad blood between Alcibiades and Agis, it seemed that Alcibiades decided to effectively defect to Persia from Sparta, although it is certain that he was conspiring with certain Athenian commanders in the eastern Aegean as well.

|

| Theatre of Dionysus in Athens |

The Olympic Games were held this year. Exainetos of Acragas won the stadion race for the second time.

In the year 411 the Spartans won a small naval victory in the Battle of Syme near the Carian coast, but it was not to prove crucial. The Athenians had by now gathered reasonable navy that had a base at Samos and was able to continue the siege at Chios.

Meanwhile, certain generals conspired with Alcibiades to bring him back to Athens. Alcibiades was held to have great influence with Tissaphernes and said that he could bring both Tissaphernes and the King of Persia onto the Athenian side if they could change the government of the city from a democracy to an oligarchy. The aristocrats of Athens were impoverished by the war and after the disaster of the Sicilian Expedition, were ready to try a change of government. Alcibiades was, as always, playing a type of double-game, as it is likely that he was outstaying his welcome with the satrap Tissaphernes and wanted to return to Athens at whatever cost before he fell out of favour entirely.

A number of generals went to meet Alcibiades, including Thrasybulus and Peisander, both of whom were committed democrats, but who were desperate for any way of raising funds to save the city. Alcibiades had changed his phrasing from asking for an oligarchic government to merely asking for a government other than a democracy.

|

| Vase painted by the Eretria Painter |

The Athenian forces at Samos were informed that the change in government was being contemplated, and after many protests, the Athenian troops eventually sullenly acquiesced at this as the only way to save the city. Meanwhile the generals, particularly Peisander, went on with their plans for a double coup, both at Samos, where the fleet lay, and at Athens itself. However, while these plans were afoot, their negotiations with Tissaphernes broke down, with the Persians demanding more than the Athenians felt that they could give.

Tissaphernes is described as being extremely duplicitous, but he was no more deceitful with the Greeks than they were to him or to each other. He half-supported the Spartans, half-supported the Athenians, humoured the fickle Alcibiades for as long as Alcibiades could be useful and gave the all-important Phoenician fleet to no one. It is said that the Phoenician fleet moved as far as Aspendus, but then stayed there and made no further move. It is possible that Tissaphernes had no authority to move it, and perhaps it was afterwards sent south to help crush a rebellion that was breaking out in Egypt, but it is equally likely that Tissaphernes wanted the Persian navy nearby, but felt ill-inclined to risk it for the good of either Athens or Sparta. To the Greeks he may have been the model of treachery, but he was certainly an able and trusty servant to the King of Persia.

Astyochus, in command of the Spartan navy, supported a rebellion against the Athenians in Rhodes. Shortly afterwards a revolt against the Athenians broke out on the Hellespont, supported by Spartan land troops. The Athenian navy was now stretched thin, trying to fight battles against the Spartan navy, hold the Hellespont and continue the siege of Chios, which was broken shortly thereafter.

|

| Lekythos painted by the Reed Painter |

Theramenes, son of Hagnon, was also one of the foremost of the subverters of the democracy—a man as able in council as in debate. Conducted by so many and by such sagacious heads, the enterprise, great as it was, not unnaturally went forward; although it was no light matter to deprive the Athenian people of its freedom

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 8, written circa 400BC

The new council immediately sent messages to Agis II at Decelea to ask him for peace terms. Agis instead marched against the city to attack it, but even in the middle of a coup, the Athenians still manned their walls and drove off the Spartan king. Seeing this Agis opened negotiations, as this was still a very real chance to end the war.

During the coup, the orator Andocides, who had been imprisoned on suspicion of desecrating the herms and who afterwards turned informer on many others, used this excuse to return to Athens. However no sooner did the wandering Andocides turn up in Athens than he was promptly imprisoned, as even the oligarchs wanted nothing to do with someone who was said to be a sacrilegious informant. They had wanted to execute him, but he had run to an altar and claimed sanctuary as soon as he realised their intentions. He was released through some means shortly thereafter and fled to Cyprus.

|

| Vase painted by the Meidias Painter |

The coup in Samos thus failed, although Hyperbolus, the last Athenian to be ostracised, was killed in the confusion. The fleet sent word back to Athens to say that they had stayed staunchly democratic. This message arrived after the coup had taken place so one of the messengers escaped the imprisonment of the oligarchs and returned to Samos to paint a lurid picture of the tyranny.

Thrasybulus was now the leader of the fleet. He was in favour of democracy and a patriot of his city. Realising the danger of the oligarchic coup in Athens, and the futility of Persian aid from Tissaphernes, he made the troops swear an oath that they would favour the democracy in future and that they would continue the war and be enemies of the Council of Four Hundred. In Thrasybulus' words, the fleet was not in rebellion against Athens; the fleet itself was Athens. If anyone was in rebellion, it was the Council of Four Hundred.

|

| Portrait of Tissaphernes from one of his coins |

As the Spartans had gone from Tissaphernes, the Athenians now made an alliance of sorts with Tissaphernes and also recalled Alcibiades to the fleet at Samos. As predicted by Phrynichus, Alcibiades cared neither for democracy nor oligarchy, but was merely interested in moving back to Athens, as his position with the Persians was becoming precarious.

This understanding between Tissaphernes and the Athenians led to an even worse breakdown of relations between Tissaphernes and the Spartans. The Spartans quarrelled with their allies, particularly Hermocrates of Syracuse, who had expected to lead the Syracusans to join in a triumphal overthrow of Athens, but instead found himself and his men locked in an ever more confusing tangle of diplomacy, manoeuvre, and treachery. Astyochus, who may have been conspiring with Tissaphernes himself, returned to Sparta, taking with him Hermocrates and some Persian representatives to argue their respective cases before the Spartans.

While the Spartan fleet was leaderless, the Athenians nearly went to war among themselves, with the representatives of the Four Hundred going from Athens to the fleet at Samos and trying to reconcile the two sides. The sailors and soldiers of the fleet were against the oligarchs and would have sailed to attack Athens had not Alcibiades intervened and said that as long as both city and fleet survived, Athens stood and might yet be reconciled, but that if either was destroyed then Athens was lost. It was perhaps the one piece of true public service that Alcibiades ever did.

Meanwhile the oligarchs in Athens were divided themselves. Moderate oligarchs like Theramenes wanted a broader franchise, while the more extreme oligarchs like Phrynichus and Antiphon would have had a smaller government than 400 if they could. The extreme oligarchs began to build a fortification in Piraeus that was believed to be a method of betraying the city to the Spartans. The people began to wonder if a broader franchise, an assembly of Five Thousand rather than a council of Four Hundred, might be better. The general Phrynichus was assassinated and his killer refused to name his accomplices even under torture. Theramenes, the moderate oligarch, now carried the day and the fortification of the Piraeus was torn down and the Five Thousand began to rule.

|

| Vase painted by the Meidias Painter |

Meanwhile another practitioner of oratory was in trouble. Antiphon of Rhamnus was put on trial for his role in the coup. He was a writer of speeches, but had never spoken in court before. This was his first time actually delivering one of his speeches. It does not survive, but Thucydides remarks that it was possibly the best speech that had yet been heard in Athens by a man fighting for their life. But even with all his brilliance, Antiphon of Rhamnus was condemned to death by the people for his role in the overthrow of the democracy.

The island of Euboea, which lies very close to Attica, had revolted at this time and Peloponnesian ships sailed past Athens to support the rebellion in Euboea. The new assembly of the Five Thousand met on the Pnyx Hill to pass emergency measures and see to the defence of the city against the new threat.

Meanwhile, the Athenians, following some Spartan reinforcements to the Hellespont, came upon the main Peloponnesian navy and prepared for battle. The two sides were nearly evenly matched, but the Athenians were slightly outnumbered. The Athenians under the command of Thrasybulus and Thrasyllus won a decisive victory after an initial setback. Because the coastline was so near, many of the Peloponnesian ships escaped, but it was nevertheless a signal victory and the first major victory that the Athenians had won since the disaster at Syracuse. The battle was known as the Battle of Cynossema and the good news was conveyed to the city of Athens, which emboldened the people and began to restore their faith in the democracy.

It is around this point that the account of Thucydides in his History of the Peloponnesian War breaks off, literally midsentence. We know that the book itself was still being written perhaps a decade later, so why it should end in this manner is simply not known. It is nevertheless to be regretted that he did not write more. Putting down the writings of Thucydides is like bidding farewell to an old friend.

|

| Oxyrhynchus papyrus fragment of Thucydides work |

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 8 breaking off mid-sentence, written circa 400BC

Others have taken up the burden of writing at this point, most particularly Xenophon, who begins his book "Hellenica" at this point. Another anonymous historian whose work is only preserved in fragments wrote a similar history, which is generally known as the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia.

The Athenians now established a base at Sestos, while the Spartans, who were at Abydos, summoned reinforcements. These reinforcements were caught by the Athenians and the Spartan navy had to sally out and attack the Athenians. The Athenians looked as if they might be beaten when Athenian reinforcements led by Alcibiades arrived in the nick of time from Samos. This time the Spartans suffered heavy enough casualties to even the odds between the two fleets. This battle was known as the Battle of Abydos.

In this year, Sicily continued in a disordered state and the cities of Selinus and Segesta went to war. Segesta had been allied with Athens in the time of the Sicilian Expedition and had thus been wary of causing any offence to any of her neighbours. However the Selinuntines used this caution as a good excuse to carve away large swathes of territory for Segesta. Segesta appealed to Carthage. The Carthaginians were wary of becoming too involved in Sicily, but after initially offering to allow Syracuse to arbitrate, they agreed to send a supporting force to Segesta.

In this year it is likely that Euripides produced the play Helen. It has survived to us and is a play strongly denouncing the evils of war. These evils must have been well known by now to the Athenians.

|

| A statue from an earlier period depicting a Spartan girl |

In the year 410 Seuthes I of Odrysia, the most powerful ruler of the many potentates among the Thracian tribes, died. He was succeeded as ruler of the Odrysian confederation by Amadocus I, who was later engaged in conflicts with the warlike Triballi tribe of Thracians on the southern bank of the Danube. Amadocus appointed a general named Seuthes to guard his domains on the Aegean shore. However, this general later made himself an independent king, known as Seuthes II, and fought against his supposed overlord.

Around this time Evagoras made a surprise attack on Salamis in Cyprus and captured the city from the Phoenicians that had controlled it. Evagoras' family had previously controlled Salamis so he had a lot of local support, but feared retaliation from the Persian Empire. To try and bolster his weak position, Evagoras sent to the Athenians and made some form of an alliance with them. He also attempted to conciliate the Persians and was not at this time at open war with them.

In this year, Corcyra, which was one of the reasons that the Athenians had gone to war in the first place and which had proved singularly useless in the war, had yet another coup attempt. The oligarchs tried to retake control of the city once more, perhaps reasoning that the Athenians could no longer intervene in the favour of the commoners. The Athenians did in fact intervene, with their general Conon sailing from Naupactus to Corcyra and helping the commoners destroy the oligarchs in yet another massacre. Corcyra continued to be useless to the Athenian cause thereafter.

Euboea, which was in revolt against Athens, appealed to Thebes to assist them in making a causeway to join Euboea to Boeotia between the cities of Chalcis and Aulis, where the channel was narrowest. This was quite a good idea and causeways were stretched out from the land until only a short channel was left for the sea, which could be bridged easily. The Athenian general Theramenes was dispatched with a naval force to put a stop to this, but he was unable to.

|

| Stater of King Archelaus I of Macedon |

The Athenians had won a victory in the previous year at Abydos, but the Peloponnesians and their allies, under the command of Mindarus and with the assistance of the Persian satrap Pharnabazus, had made good their losses. They once again matched the Athenian fleet in numbers. Pharnabazus was also able to assist them with some land-based forces. While the Spartans threatened the sea traffic from the Black Sea, they had their foot upon the windpipe of Athens, as it was through these straits that the grain ships bound for Athens had to pass. The Athenians had to somehow defeat the Spartans here.

The Spartans launched an attack on Cyzicus, between the Bosphorus and the Hellespont. The Athenians slipped by in the night and hid their fleet near the island of Marmara. Theramenes and Thrasybulus each commanded large squadrons while Alcibiades led a small squadron within sight of the harbour of Cyzicus. Knowing that this would be an irresistible target to the Spartan commander Mindarus, the Athenians lingered in the area before turning to flight once the Spartan navy put to sea.

|

| Reconstruction of a trireme |

The Athenians had landed some troops the previous night and Theramenes landed his squadron near where the friendly troops were. Meanwhile the ships of Thrasybulus and Alcibiades were beached and their troops attempted to pursue the Spartans. The Persians tried to drive them back into the sea, but the reinforcements under Theramenes arrived in time to catch the Spartans and Persians between the two forces. Thoroughly out-generalled, the Spartan commander Mindarus was slain after hard fighting and the Spartans and Persians fled inland, leaving the Athenians in possession of not only their own fleet, but most of the Spartan fleet. The only exception of the Syracusan vessels, which had been burned before abandonment.

The Athenians had to put to sea quickly after the battle, as Pharnabazus was hastening to the scene with a strong force of cavalry, but they had won a brilliant victory. The Athenians now retook Cyzicus. While the Battle of Cyzicus was a dramatic victory for the Athenians, they were quite short of funds and this stopped them from following up their victory.

|

| Athenian grave stela |

Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, Book 13 written circa 40BC

The Persian satrap Pharnabazus must have been annoyed with the poor showing of both his own troops and the vaunted Spartans and their allies, but he is said to have encouraged the survivors and to have ordered them paid and to await new orders. He promised to assist them in building new ships. It was around this time that the news came from Syracuse that the new Syracusan regime, led by Diocles, had banished the captains in the east, particularly Hermocrates. New captains arrived from Syracuse to continue the war, while Hermocrates went to Pharnabazus, who gave him large sums of money to aid in his revenge.

It is said that the Spartans sent a letter back to Sparta, laconically stating "Ships gone. Mindarus dead. Men starving. Send orders." It is hard to know if this is true or just one an anecdote. It is hard to see how they could be starving considering that Pharnabazus was supplying them. I suspect that this is legendary.

The Spartans were deeply concerned with the outcome of the battle however. A few years earlier Athens had been deemed to be on its knees. Now the courage of the Athenians had so changed the situation that the Spartans sent an embassy offering terms of peace. Even the Spartans must have grown tired under the weight of this endless war.

It almost appears inexplicable now, but the Athenians refused the Spartan terms. A popular leader named Cleophon spoke to them of the victories that had been won and that they might yet win. Athens viewed itself as the full equal of Sparta, and to have fought this long war and to have gained no advantage whatsoever seemed to be intolerable to the Athenians. Peace was refused and the long war ground onwards.

|

| Temple in Segesta, Sicily |

The Carthaginians and Segestans caught the Selinuntines as they were raiding Segestan territory and inflicted a severe defeat on them. Selinus now appealed once more to Syracuse, who offered to help, but did not in fact do anything. Meanwhile Hannibal Mago was gathering a much larger force in Africa to prepare for the next stage of the war.

In this year, Plato the comic poet (not Plato the philosopher) won the prize for Comedy in the Great Dionysia festival. Like most plays from this time, it sadly does not survive.

Around this time the sophist brothers Euthydemus and Dionysodorus were said to have flourished in Athens. They spoke and lectured together as a team and are satirised by Plato in one of his dialogues (named after Euthydemus) where Socrates is said to have questioned the brothers and found most of their rhetorical excellence to be composed mainly of cheap pseudo-logical sleights of hand.

|

| Coin of Selinus in Sicily |

If we are mentioning people connected to Socrates, now is as good a time as any to mention Xanthippe, who was the wife of Socrates. She is seldom mentioned in the works of Plato or Xenophon, but in certain later writers such as Diogenes Laertius, she is depicted a shrewish wife who is constantly scolding or nagging her husband. This is a harsh reputation to go down in history with, but Socrates is said to have borne it rather meekly, treating the scolding as like the later St Paul's "thorn in the flesh", something unpleasant, but to be stoically endured nonetheless. Xanthippe leaves behind no words of her own, (it is not clear that she was literate) and thus cannot set the record straight. It must be admitted that Socrates was, according to all the sources, a rather singular gentleman and one who occasioned much annoyance even among his dearest friends. I can therefore sympathise with his long-suffering wife and feel she has been much maligned.

|

| Athenian grave stela |

The Meidias Painter also flourished around this time. He was an Attica red-figure vase painter who painted in the Rich Style and whose works have survived to the present day.

And thus the period draws to a close. The decade was tumultuous, beginning with the uneasy Peace of Nicias still in force before the horrendous losses for the Athenians in the Sicilian Expedition. This was followed by coups in Athens, treachery and double-dealing on all sides in Ionia and finally a recovery of sorts by the Athenians, allowing the long war to finish its sad and sorry course. I will continue the story of the history of the Greek world in the next blog.

|

| Athenian grave stela |

Aristophanes, The Clouds, written 423BC

Sophocles, Electra, written circa 419BC

Euripides, Heracles, written circa 416BC

Antiphon of Rhamnus, Orations, written circa 416BC

Antiphon the Sophist (possibly identical to Antiphon of Rhamnus), Fragments, written circa 416BC

Euripides, Trojan Women, written circa 415BC

Euripides, Ion, written circa 414BC

Aristophanes, The Birds, written 414BC

Euripides, Electra, written circa 413BC

Andocides, On His Return, written 411BC

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, written circa 400BC

Plato, Symposium, written circa 385BC

Xenophon, Hellenica, composed circa 355BC

The Parian Chronicle, written circa 216BC

Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, written circa 40BC

Plutarch, Life of Nicias, written circa AD100

Plutarch, Life of Alcibiades, written circa AD100

Pausanias, Description of Greece, written circa AD150

Secondary Sources:

Historical eruptions on Mount Etna

Catalogue of Greek coins

Related Blog Posts:

Greece 429-420BC

419-400BC in the Near East

419-400BC in Rome

409-400BC in Greece

No comments:

Post a Comment